Elgin lied to the Select Committee of Parliament that purchased the marbles.

Professor Rudenstine has established that Elgin lied to Parliament by stating that he (Elgin) personally travelled to Athens with the second firman. This revelation by the Professor is substantiated by correspondence from Hunt to Richard William Hamilton stating that he (Hunt) was leaving for Athens within days with a new firman. It is known from Hunt’s correspondence to Elgin that Hunt took the letters allowing Elgin’s party to dig, (the so-called second firman) to the Voivode, or governor of Athens in July 1801.

Elgin however stated in his evidence to Parliament in 1816 that the second firman was addressed by the Porte to the local authorities in Athens “to whom I delivered it”. LINK

In addition to the overwhelming case made by Prof. Rudenstine, there are records of two further statements that contradict Elgin’s sworn evidence to the Select Committee.

The first statement is recorded in the letters of the Countess of Elgin (hereinafter Mary Nisbet), who stated that Elgin, her husband did not set out for Athens to see the effect of the new firman which Pisani obtained in 1801, until 1802, or as she put it: “a whole year later, Lord Elgin was at last able to visit the scene of the operations himself”. LINK

Mary Nisbet then goes on in the same letter to her mother dated 10th April 1802 to make reference to her, and her husband’s departure for Greece: “We sailed from Constantinople monday evening the 28th of March”, LINK and later in the same letter states: “It was between 8 and 9 O’clock when we arrived in Athens“(3rd April 1802). LINK

The second piece of evidence indicating that it was Hunt, as opposed to Elgin, who took the second firman to Athens can be found in Hunt’s evidence to Parliament, when in answer to a question regarding permission to pull down a house, Hunt responded: “No; I am confident no such permission was in the fermaun I took to Athens, though it contained general permission to excavate near the temples“. LINK

This evidence from Hunt, who was the last witness to testify to the Committee, together with the letters of Mary Nisbet and Hunt (to Hamilton and Elgin) flatly contradict Elgin’s testimony to the Select Committee.

It could not be said that Elgin was confused about his first visit to Athens when he was in the words of his wife “at last to visit the scene of the operations himself“. To see the Parthenon being dismantled is something that he would have remembered.

Elgin’s Parthenon disinvestment squad in action as depicted by the BBC

Elgin’s Parthenon disinvestment squad in action as depicted by the BBC

So Elgin’s claim to have taken the firman to Athens was an intentional deception made to give him the appearance of being someone personally knowledgeable about the firman. Elgin deliberately deceived the committee to assuage their concerns about the propriety of his actions in Athens, and he did so in order that he might sell the committee his collection for financial gain. Elgin lied to Parliament.

Under normal circumstances one of the two witnesses who contradicted Elgin’s lie that he took the firman to Athens would not have been heard. We know from Hunt’s evidence that he was not scheduled to give evidence to the committee. Hunt was the last witness, called unexpectedly, to give evidence that contradicted Elgin’s statement and confirmed a well documented fact confirmed in Mary Nisbet’s contemporaneous letters (now held in private by the British Museum), that Hunt, rather than Elgin took the firman to Athens. Mary Nisbet, estranged from Elgin, was not called to give evidence and her letters were made public by her family (in an edited version) in a book published by a relative in 1926.

The Select Committee should have spotted the contradiction between Elgin’s evidence and Hunt’s regarding the date and identity of the bearer of the firman to Athens, but perhaps faced with the embarrassment of exposing their former Ambassador as a liar and a thief was a step too far. How would the government have dealt with the humiliation that this would have brought? They could not have returned hundreds of tons of marble and other items to a foreign country that was occupied by Turkey, a nation that was an ally, but one that resented British influence in their territory. The logistics of such reparation in those days would have been massive as it had taken a small fleet of Royal Naval and merchant ships (33 in number) several years to bring the marbles to this country in the first place. LINK

However the mute acceptance by the committee of Elgin’s obvious lie is not their worst omission. The most astonishing thing about the Select Committee examination of Elgin’s claims that he had authority to remove the marbles and other items that formed his collection is that the main piece of evidence was not central to this process. To have a parliamentary committee of inquiry and examination without the firman being the centre-piece of that process beggars belief. This glaring omission supports the theory that the Select Committee knew that Elgin was a liar and a thief, but he was their liar, their thief, and as Part II of the Report concludes: if Elgin had not taken the marbles the French would have. The Select Committee apparently accepted Elgin and Hunt’s permissive interpretation by recollection of the terms of the firman in order to give them a ‘fig leaf’ of legitimacy to cover their naked embarrassment.

It should come as no suprise to those who have studied the actions of Thomas Bruce that he was a glib liar. Before he faced the Parliament’s committee in 1816, he had began the process of touting his loot for sale by writing to Prime Minister, Spencer Perceval, on 31 July 1811, at which time he told a bare-faced lie about “accidentaly” meeting the Captain Pacha on the Trode, when in fact he had yet to meet that man on the one occassion he visited that spot. See: “Comparing 4 editions of Elgin’s Memorandum” LINK

Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin & 11th Earl of Kincardine 1766–1841

Born at Broomhall, Fife he was 33 when he married Mary Nisbet, a wealthy heiress some 12 years his junior, in March 1799, shortly before setting off to serve as ambassador to the Porte at Constantinople.

Elgin was plagued by syphilis, which ate into his nose till he lost it, and this together with the age difference may have caused his young wife to take a lover when Elgin was imprisoned in France while on his way home after serving his term as Ambassador. Elgin later sued the lover (now husband to his ex-wife) through both the English and Scottish Courts for monetary compensation for seducing his wife, an act that scandalised high-society of the day.

Elgin then married Elizabeth Oswald who bore him five sons, one of whom James the 8th Earl, like his father before him left his mark on the world of art.

In October 1860, James (Above) as British High Commissioner to China ordered the sacking (by 3,500 soldiers) of the Old Summer Palace in Beijing after the Second Opium War. The fire that followed the looting burned for three days consuming the vast palace complex containing China’s most treasured buildings and art works.

In October 1860, James (Above) as British High Commissioner to China ordered the sacking (by 3,500 soldiers) of the Old Summer Palace in Beijing after the Second Opium War. The fire that followed the looting burned for three days consuming the vast palace complex containing China’s most treasured buildings and art works.

Most enlightened people in Europe were outraged by the sacking and burning of the Old Summer Palace. French author Victor Hugo aired his revulsion by way of a letter of reply to an inquiry as to how he viewed the looting.

In this powerful letter Hugo described James, the 8th Earl of Elgin’s barbarism, as being even worse than that of his father. He wrote: “Mixed up in all this is the name of Elgin, which inevitably calls to mind the Parthenon. What was done to the Parthenon was done to the Summer Palace, more thoroughly and better, so that nothing of it should be left. All the treasures of all our cathedrals put together could not equal this formidable and splendid museum of the Orient.” LINK

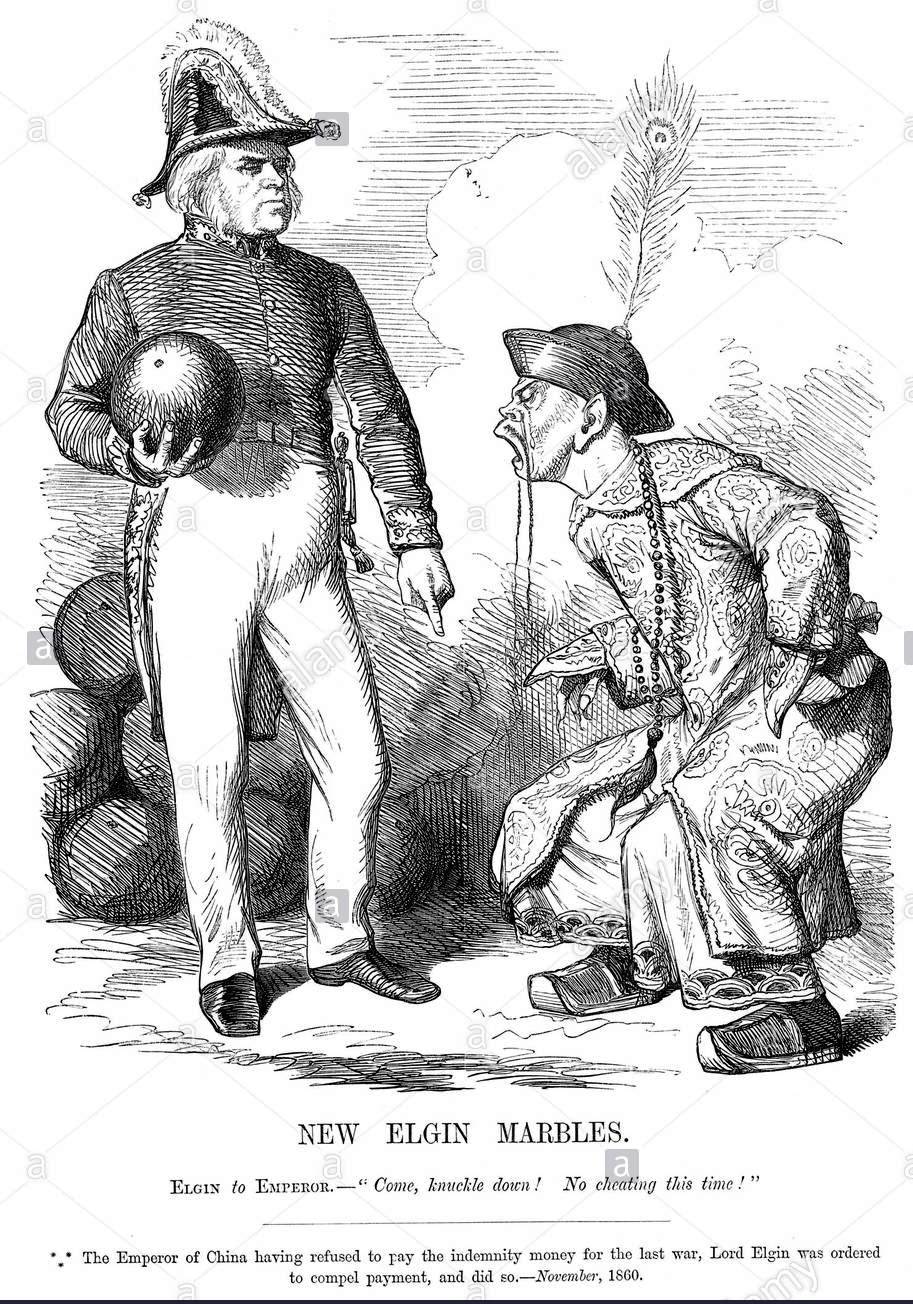

The Punch cartoon, above right, from November 1860 depicts James, 8th Earl of Elgin with cannon ball in one hand, pointing to the ground with the other while smoke billows from the burning Old Summer Palace in the background. Elgin tells the Emperor of China: “Come Knuckle Down, No Cheating This Time” (1740 English dictionary meaning: “Knuckle or knuckle down: to stoop, bend, yield, comply with, or submit to.”). This is a reference to the failure of the Chinese Emperor to pay the 8 million taels of silver that formed part of the war reparations imposed by Britain after the 1858 Treaty of Tianjin, which ended the Opium Wars. Chinese failure to promptly endorse the treaty led to Elgin ordering the sacking and burning of the Summer Palace.

The caricatures of the upright, noble and honest British diplomat, and the ugly, twisted and dishonest Chinese sovereign, reflects the arrogance of Imperial Britain in those times when she was the superpower. Today China is the superpower and her officials are seeking to identify the locations of approximately 1.5 million relics believed to be in the museums of 47 countries that benefited from the Old Summer Palace looting.