The Charges, Prisons, Petitions & Clemency

THE CHARGES

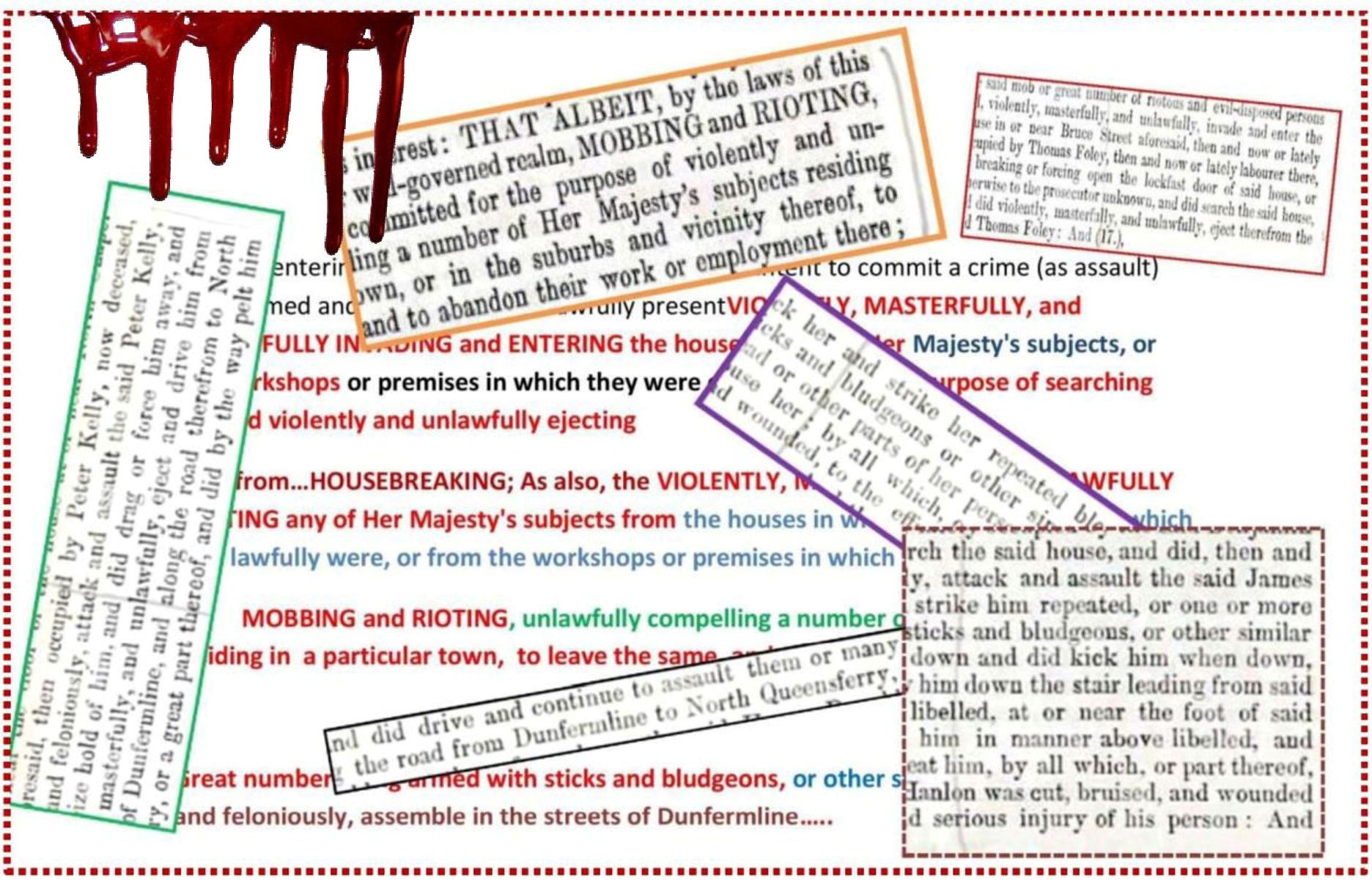

Even a quick scan of the Indictments exposes the myth perpetuated in some press reports of the trial that this was an Irish Navvy riot. It wasn’t.

No Irishmen were charged with Mobbing and Rioting. The definition of such a charge is that a group combines with a common purpose to commit violence or intimidation. The two Irishmen were charged separately with Assault, Peter Cooney (to the danger of life) acting alone, and Charles Wynn acting with three other persons unknown, during an affray in Bruce Street Dunfermline late on the Saturday night of June the 22nd 1850. Indictments of Peter Cooney & Charles Wynn

There were three victims of the Irishmen’s assaults: David Anderson, James Johnstone (a 23 year old Irish coal hewer, not to be confused with a 54 year old Scottish man of the same name, and occupation, later convicted of the mobbing and rioting that followed*) and Thomas Chalmers. *Correction following sight of trial papers.

By contrast twelve native inhabitants of Dunfermline were charged (in three separate indictments) for their part in the events of the Monday following the Saturday night affray with:

1/ Mobbing and Rioting.

2/ Violently, Masterfully& Unlawfully Invading & Entering the dwelling houses of Her Majesty’s subjects.

3/ Housebreaking.

4/ Violently, Masterfully& Unlawfully Ejecting Her Majesty’s subjects.

5/ Assault causing serious injury.

Indictment of Henry Donaldson & others

Indictment of Adam Baxter & others

Indictment of Alexander Black Snr. & others

The total number of Her Majesty’s (mostly Irish) subjects, who were victims of the Dunfermline natives’ crimes numbered at least one hundred: Recorded Irish/Scots victims of mob

The press reports of the day and subsequent historical articles give much detail of the injuries to the few victims of the two Irish navvies, but don’t report in a similar vein (with three exceptions previously noted in Part One), the many injuries to the Irish who were assaulted and evicted. This is remarkable!

One of the evicted was an elderly Irishman, Peter Kelly, a pedlar, who died within days of being forcibly evicted, assaulted and driven 10 kilometres from Dunfermline to North Queensferry, all the while being beaten and abused by the mob. If anything was newsworthy this was.

Although the press didn’t report any details of Irish victims, the indictments do. Here are just three examples:

Pedlar, Peter Kelly, (Donaldson/Baxter Indictments) (18.), “the said mob or great number of riotous and evil-disposed persons did, at or near the door of the house at or near North Chapel Street aforesaid, then occupied by Peter Kelly, now deceased, wickedly and feloniously attack and assault the said Peter Kelly, and did seize hold of him, and did drag him or force him away and violently, masterfully, and unlawfully, eject and drive him from the town of Dunfermline, and along the road therefrom to North Queensferry, or a great part thereof, and did by the way pelt him with stones or other missiles and beat him with their fists, and with sticks or similar weapons, and did otherwise maltreat and abuse him, to the severe injury of his, person.”[Peter Kelly died in the space of a few days after his beating and forced march. Peter was cited to appear as a prosecution witness, but when the list of witnesses was published a few day later by the Advocate Depute he was noted as “deceased” ]

Housewife, Catherine Macfferty, (Donaldson/Baxter Indictments) (20.), “the said mob or great number of riotous and evil-disposed persons did, wickedly and feloniously attack and assault the Catherine Macafferty or Lyons or Lyness, wife of the said Benjamin Lyon or Lyness, and did kick her and strike her repeated blows with the fist, and with sticks and bludgeons or other similar weapons, on or about the head or other parts of her person, and did otherwise maltreat and abuse her; by all which, or part thereof, she was cut, bruised, and wounded to the effusion of her blood, and serious injury of her person.”

Weaver, James O’Hanlon, (Donaldson/Baxter Indictments) (18.) ” “having fled to the house in or near the Rhodes Building aforesaid, then and now or lately occupied by Benjamin Lyons or Lyness, then and now or lately weaver there to escape from the violence of the said mob or great number of riotous and evil-disposed persons, the said mob or great number of riotous and evil-disposed persons did follow him there and did, violently masterfully, and unlawfully, invade and enter the said house then and now or lately occupied by the said Benjamin Lyons or Lyness, and did search the said house, and did then and there, wickedly and feloniously, attack and assault the said James O’Hanlon or Hanlon, and did strike him repeated, or one or more blows with the fist and with stick and bludgeons, or other similar weapons, and did knock him down and did kick him when down and did forcibly drag or throw him down the stair leading from said house and did; time above libelled, at or near the foot of said stair again attack and assault him in manner above libelled, and did otherwise abuse and maltreat him, by all which or part thereof, the said James O’Hanlon or Hanlon was cut, bruised, and wounded to the effusion of his blood and serious injury of his person:”

In Scots law an Indictment is the court document that sets out criminal charges where the offences are to be dealt with in solemn proceedings (serious criminal charges heard before a judge and jury), whereas less serious offences are dealt with in summary proceedings.

The above extracts from the indictments therefore are serious matters, but they are only some of the many brutal acts of the mob against many innocent people, predominately Irish, who played no part in the Saturday night affray. But even these large numbers of victims don’t tell the full story, because as well as the acts detailed in the indictments, witnessed by many, there were others, which would have gone undetected.

As evidence of this underestimate, the newspapers of the day reported several instances of brutal treatment to Irishmen that didn’t feature in the indictments (Two agricultural labourers and a weaver Frederick Linnen), so it must be the case that the violence was even greater than that from which charges resulted.

As well as these known acts of violence against those thought to be Irish, there must have been many more that were unknown to the authorities, seen, but not reported, due to those who witnessed them being afraid to come forward for fear of reprisals. And in the 1850 Dunfermline riot, where the mob numbered between two to three thousand (a large percentage of the small town’s circa. 10,000 population), the rioters would almost certainly have known anyone who dared to speak up against them.

This fear of being marked out for reprisal by a secretive, violent mob, defeating the ends of justice was noted in the Fifeshire Journal regarding an earlier 1845 riot thus: “We are glad to believe that the result of these laborious investigations will be the conviction of some of the leaders, notwithstanding the secrecy and mystery in which their crimes are involved, and the evident fear of being marked out for vengeance felt by those who may know of circumstances, the revelation of which might promote the ends of justice.” Glasgow Herald from Fifeshire Journal 1845

That the press of the day didn’t report on the many instances of violent crimes, such as those that hastened (caused?) the death of Peter Kelly is astonishing, given that the crimes against him were published in the indictments brought against the rioters.

These were crimes that were seen by at least forty nine prosecution witnesses called by the Crown to testify against the twelve accused natives, they were also seen by many others not called.

It must be assumed that these evil acts, known to so many and well worth reporting at the time, but weren’t, was due to the fact that the press viewed a death and the injuries to the Irish residents of Dunfermline as inconsequential; they simply didn’t count.

And it seems that the awful violence meted out to the Irish residents not only didn’t count as far as the press were concerned, but it didn’t count for much as far as the courts were concerned either, because the violence element of the charges in the indictments of the natives were dropped, meaning no one faced charges for assault of the Irish.

This plea bargain meant that the court would never hear from the forty nine prosecution witnesses the gory details of the assaults which led to one Irishman’s death, and serious injuries to the person and property of many.

As the legal records stand, all the Irish residents of Dunfermline who could be identified as such, had their dwelling places broken into, they were violently evicted from them, they were assaulted and driven out of a small town on a public road for 10 kilometres all the while being stoned and abused in broad daylight, in the presence of Provost Kinnis and Bailies Johnston and Ireland plus sixty special constables, by……… persons unknown.

Again, one is left to assume that these evil acts, which should have incurred the righteous wrath of the Scottish justice system, but didn’t, was due to the fact that the legal authorities, like the press, viewed the death and injuries to the Irish residents of Dunfermline as inconsequential; they simply didn’t count.

PRISONS

Following the High Court trial at Perth the convicted men were taken to prison to serve the various terms handed down by the Court.

The twelve Dunfermline natives and one Irish navvy, Charles Wynn, were sent to Perth Prison where male prisoners worked as shoemakers, tailors, weavers, and mat makers.

The other Irish navvy, Peter Cooney, who was sentence to be transported beyond the seas for seven years, was first remanded in the Dunfermline Prison pre-trial, then returned there after his trial, spending a total of one hundred and seventy seven days there, three months of which were spent “separately confined”. He was employed in “teasing ropes”.

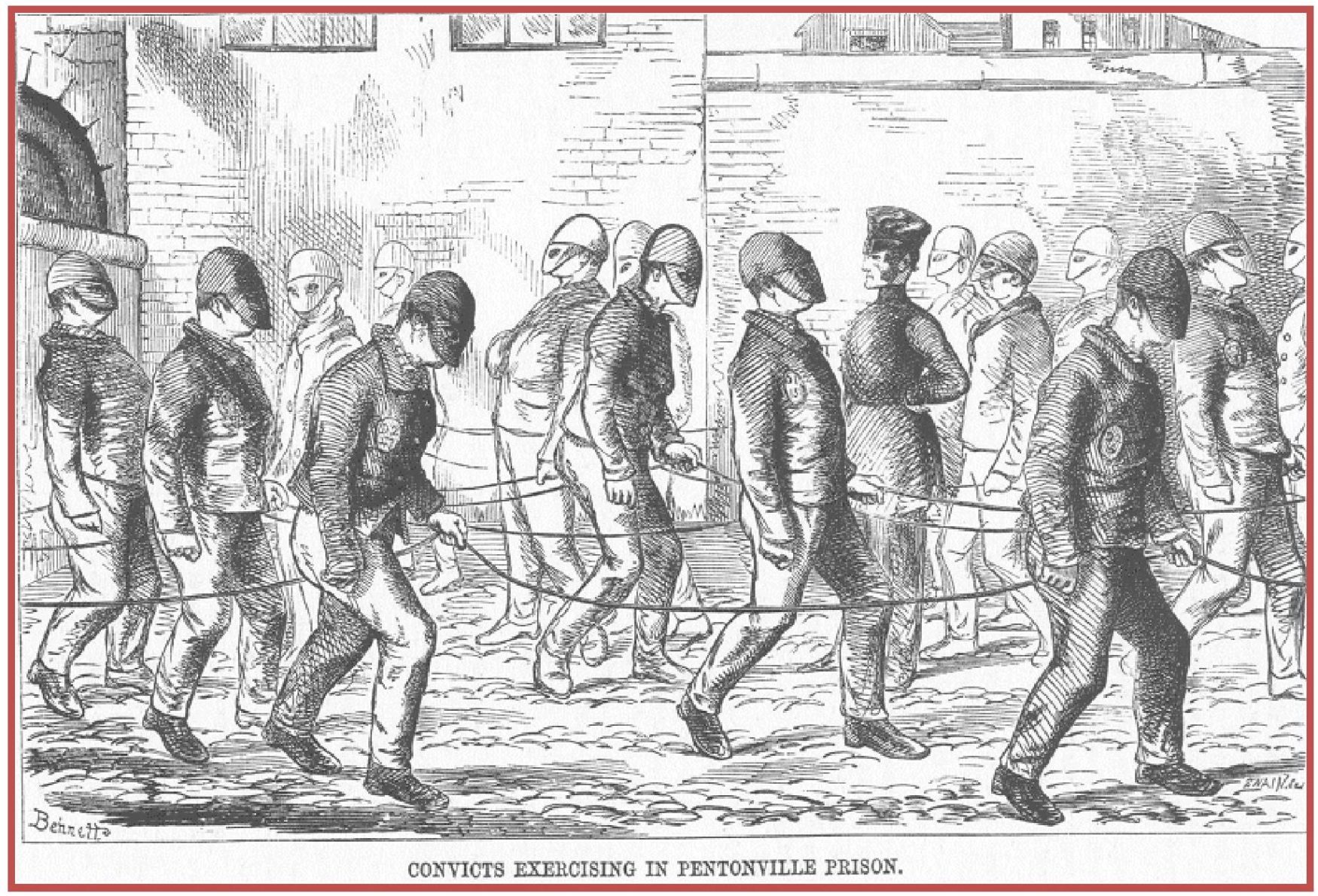

After his time in Dunfermline Prison Cooney was sent to England and was received into Millbank Prison on 21st December 1850. This prison housed male convicts serving the first (probationary) part of their sentence in “separate confinement”. This involved total isolation in silence and being required to wear face coverings at all times. Despite this, his conduct in this prison was classed as “Good”, and he was transferred to Pentonville Prison on 8th February 1851.

Pentonville Prison, like Millbank, operated on the Model Prison “separate system“, an experimental, but inhumane system that caused many prisoners to go mad and be sent to Bedlam, and many others to take their own lives, to such an extent that this experiment was eventually dropped towards the end of the 19th century. Prisoners, Insanity and the Pentonville Model Prison System

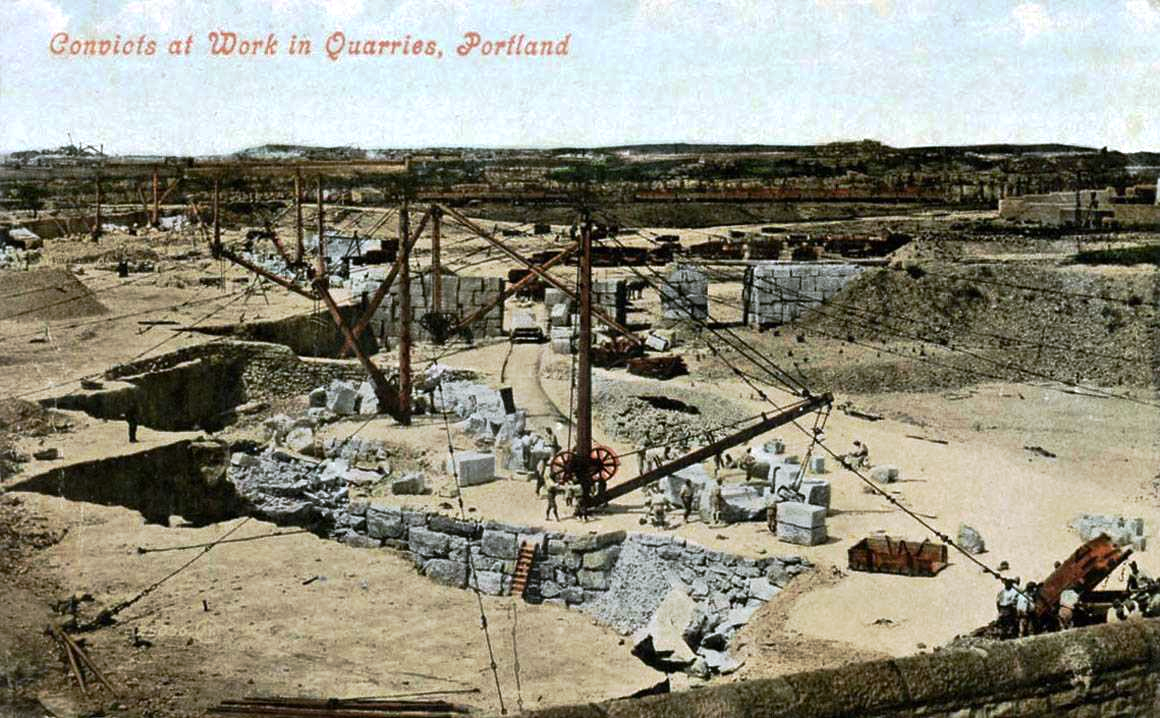

After his nine month assessment in Pentonville where again his conduct was “Good” Cooney was considered suitable for public works, thus postponing his transportation, and was sent to Portland Prison, Dorset, where he worked in the quarry and on the sea-front, helping to build the breakwater of a harbour for Royal Navy vessels that was being constructed at this time.

The healthy outdoor work at Portland must have been a welcome relief to Cooney, after having spent more than a year of mind-numbing seclusion and silence, first at Dunfermline, then Millbank and Pentonville.

Stone quarrying, dressing and erecting masonry would have been almost identical work to the work navvies did on the Stirling to Dunfermline railway bridge viaducts, like those at Buffie’s Brae, Dunfermline and Comrie Dean, Blairhall, and would have been second nature to a young strong Irish navvy like Cooney.

PETITIONS

The First Petition

While the twelve Dunfermline natives and Irishman Charles Wynn were weaving away in Perth Prison a petition was subscribed by residents of Dunfermline and district seeking the early release, on compassionate grounds, of one of their number, coal miner, Alexander Black Senior. This extraordinary development came about on June 7, 1851.

Nothing extraordinary about that?

Well there is when the petition was drawn up, not by the lumpenproletariat, the mob who had helped Black evict the Irish miners at Townhill, but by the movers and shakers in Dunfermline society.

Provost Kinnis who had first read the Riot Act to the rioters, Bailie Ireland, who had sworn in special constables at the start of the riot and had followed the mob the six miles to the Burgh boundaries, John Bonnar, the Burgh Magistrate, who would have remanded into custody those accused of Mobbing and Rioting prior to their trial at the High Court in Perth, the Minister and assistant Minister of the prestigious Abbey Church, as well as a host of manufacturers/merchants all signed their support for the petition.

The list of signatories to the petition for clemency reads like a ‘Who’s Who’ in Dunfermline and includes a name that featured large in all the 1830s and 1840s riots, Andrew Carnegie’s uncle, Thomas Morrison, now a Bailie and Burgh Treasurer, and another relative of Andrew Carnegie his uncle George Lauder, said by the millionaire to be his greatest influence in life. Petition of the magistrates & other inhabitants of Dunfermline

And if the signatories to the petition did not give it sufficient gravitas it was presented to the Home Secretary, on the petitioners’ behalf, by no less a person than the Member of Parliament for Dunfermline, Mr. John Benjamin Smith, of the Liberal Party.

When the petition was received by Sir George Grey, the Home Secretary, it was forwarded to Scotland’s Lord Justice Clerk, Lord Hope, accompanied by an explanatory letter from one of the trial judges, Lord Ivory, for him to review and report back on.

The Second Petition

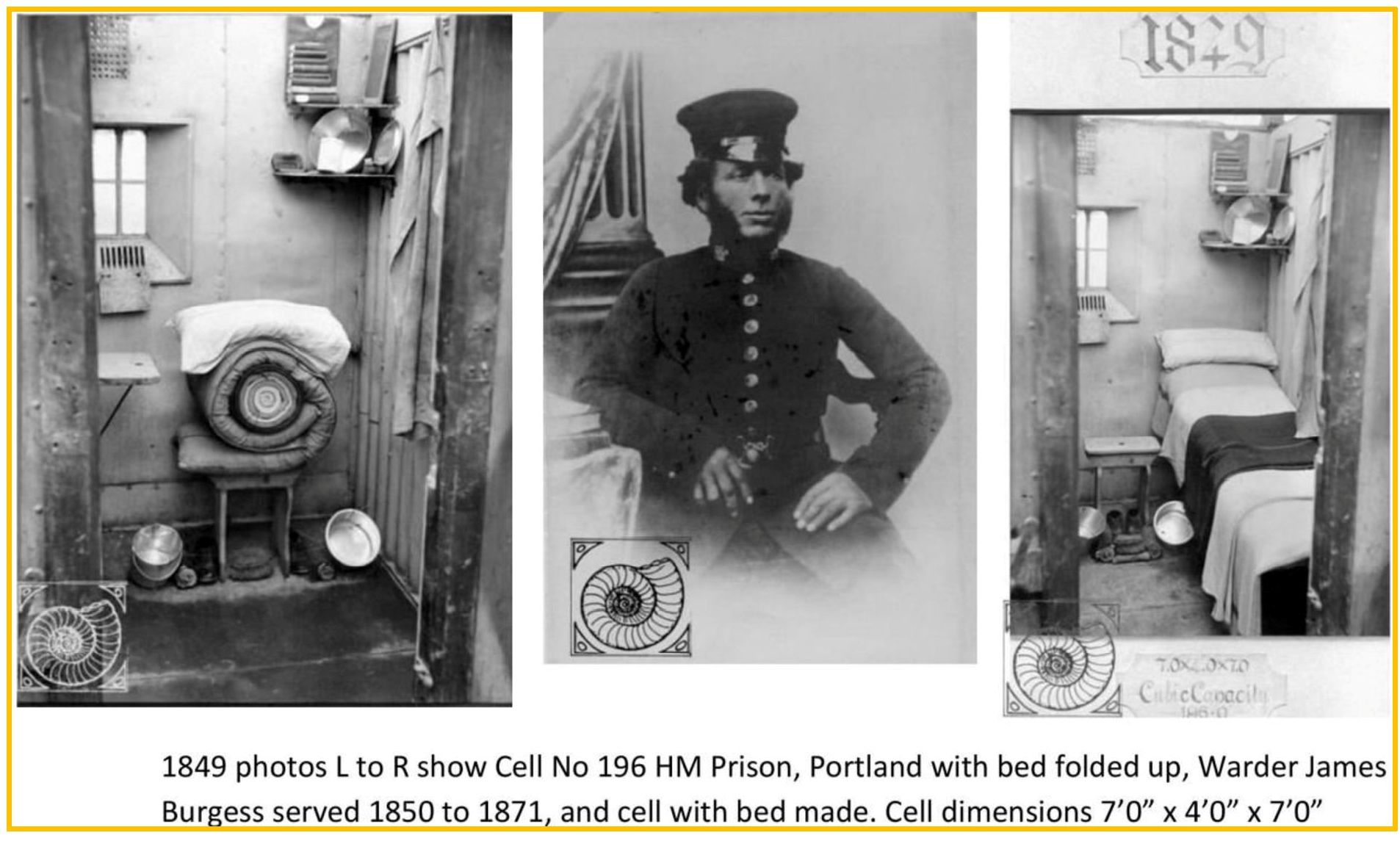

A second petition for clemency was raised in March 1852. This one was from a lone petitioner, the former Irish navvy, Peter Cooney, now a convict in HM Prison Portland, Dorset.

Unlike the one for Alexander Black, Cooney’s petition didn’t have a host of eminent Dunfermline citizens supporting it and testifying to his good character. But it did have reports from the prison authorities at the four prisons he had been held in, including one dated 19th December 1850, by Thomas Gillespie, the Governor of Dunfermline Prison where Cooney had spent “three months separately confined”.

Mr Gillespie gave a less than ringing endorsement of his Irish inmate stating that he possessed “intelligence very limited” and “could read a little” adding “nothing is known regarding the convicts character he having been a very short time in the neighbourhood”. The last statement was a strange one to make by someone, who with one warden and his wife as matron, had been the official guardian of Cooney at the small, twelve male cells, Dunfermline Prison, for almost six months. Dunfermline Prison

Nor did Cooney have the benefit of a legally trained advocate to draft his plea, or an eminent politician to present in on his behalf to the then Home Secretary, Spencer Horatio Walpole. He also had the added difficulty of writing in his own hand using a language that was foreign to him (Gaelic was the common language in Monaghan).

Despite all these handicaps, a prayer for clemency was written from a cramped prison cell in Portland Prison by Peter Cooney. In his plea he detailed how prosecution witnesses to his alleged assault of David Anderson had repeatedly failed to identify him; how he had been tried without a lawyer and without witnesses for his defence, and how a defence fund collected among his navvy colleagues to allow him to produce witnesses at Perth (a day’s coach trip from Dunfermline) had been misappropriated. Petition of Peter Cooney

Peter Cooney, wrote his prayer for clemency to the Home Secretary, Spencer Horatio Walpole from a cell like the one pictured below.

CLEMENCY FOR ALEXANDER BLACK?

The task of the Lord Justice Clerk in considering whether or not to recommend to the Home Secretary that he exercise clemency in the case of Alexander Black Senior (a case not known to him), necessitated him being appraised of the circumstances of the case by one of the trial judges. This clarification was directed by the Home Secretary in the form of an explanatory letter from Lord Ivory. Ivory to Hope letter

In his letter to the Lord Justice Clerk, Lord Ivory sought to explain his (and his fellow judge Lord Mackenzie’s) decision as to Black’s sentencing. The letter was couched in defensive terms, as if he knew the decision not to sentence any of the Dunfermline natives to transportation for crimes of such magnitude was anomalous.

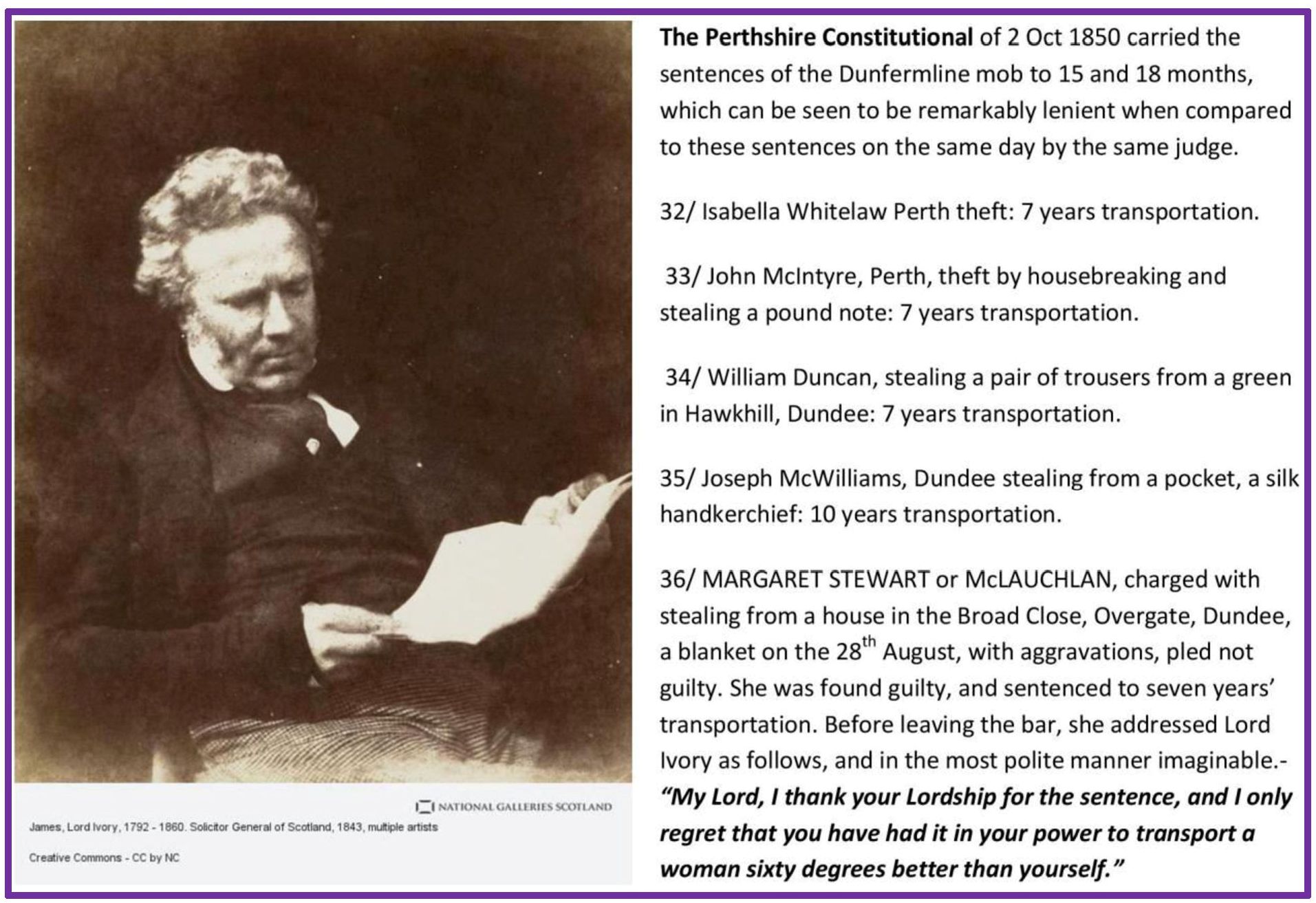

Extracts from the Perthshire Constitutional of 2 October 1850 referred to above.

Extracts from the Perthshire Constitutional of 2 October 1850 referred to above.

Puzzlingly, the reason offered by Lord Ivory for the failure to transport any of the twelve Dunfermline men was stated as being because the Perth Prosecutor had charged so many native inhabitants, who had all pleaded guilty, and so few Irish, because, he presumed, of difficulty in identification.

Lord Ivory must also have been dealing in presumption rather than fact when he misled the Lord Justice Clerk by stating that the twelve native inhabitants had “characters that were otherwise unimpeached” prior to the riot. This was untrue. It was the case that two of them, James Johnstone, and Adam Baxter, had convictions for assault prior to the Perth hearing. Convictions before 1850

Lord Ivory also hinted that it would have caused further unrest among the troublesome Dunfermline townspeople if he sentenced the twelve natives to transportation. This thorny issue caused him and fellow judge Lord Mackenzie to delay sentencing the twelve by one day as they pondered their predicament of how to deal with them. He wrote:

“It appears from my notes of the Evidence that though only one Prisoner was brought to trial, in each of these cases (from difficulty, I presume in identification) there were many more, and all Irish engaged in the cases of assault. – and that indeed the cases had a good deal, themselves of the later general outbreak of Mobbing and Rioting which was presented in the Indictment of the native inhabitants. There is every reason to believe that the latter- especially the lower classes of them-were very much excited by what had there taken place, – and being considerably intimidated some were then induced to combine, in order to rid themselves of the Irish altogether.”…..

“Had it not been that the Perth Procurator brought up so many for sentence, the punishment awarded might have been more severe. As it was, we meditated whether transportation should be applied to one or more of the prisoners. But as all had wisely pleaded Guilty, we had no room for making distinction. And we naturally shrank from transporting twelve poor people, – whose characters were otherwise unimpeached, – and who had been carried away, it is probable, in a moment of impulse and excitement.-“

It is apparent from his letter that Lord Ivory had some sympathy for the twelve native rioters who he described as “poor people” (a Masonic phrase from 3rd Degree obligations, regarding helping a brother in distress), and “shrank” from transporting them, but had little hesitation in transporting a large number of his own townfolk (he was native to Dundee) to transportation on the same day for trivial offences compared to those of the Dunfermline mob.

Lord Ivory also accepted that the twelve poor people felt intimidated by the Irish and their violent responses to this fear were not planned or calculated, but rather were “much excited” reactions taken in the heat of the moment.

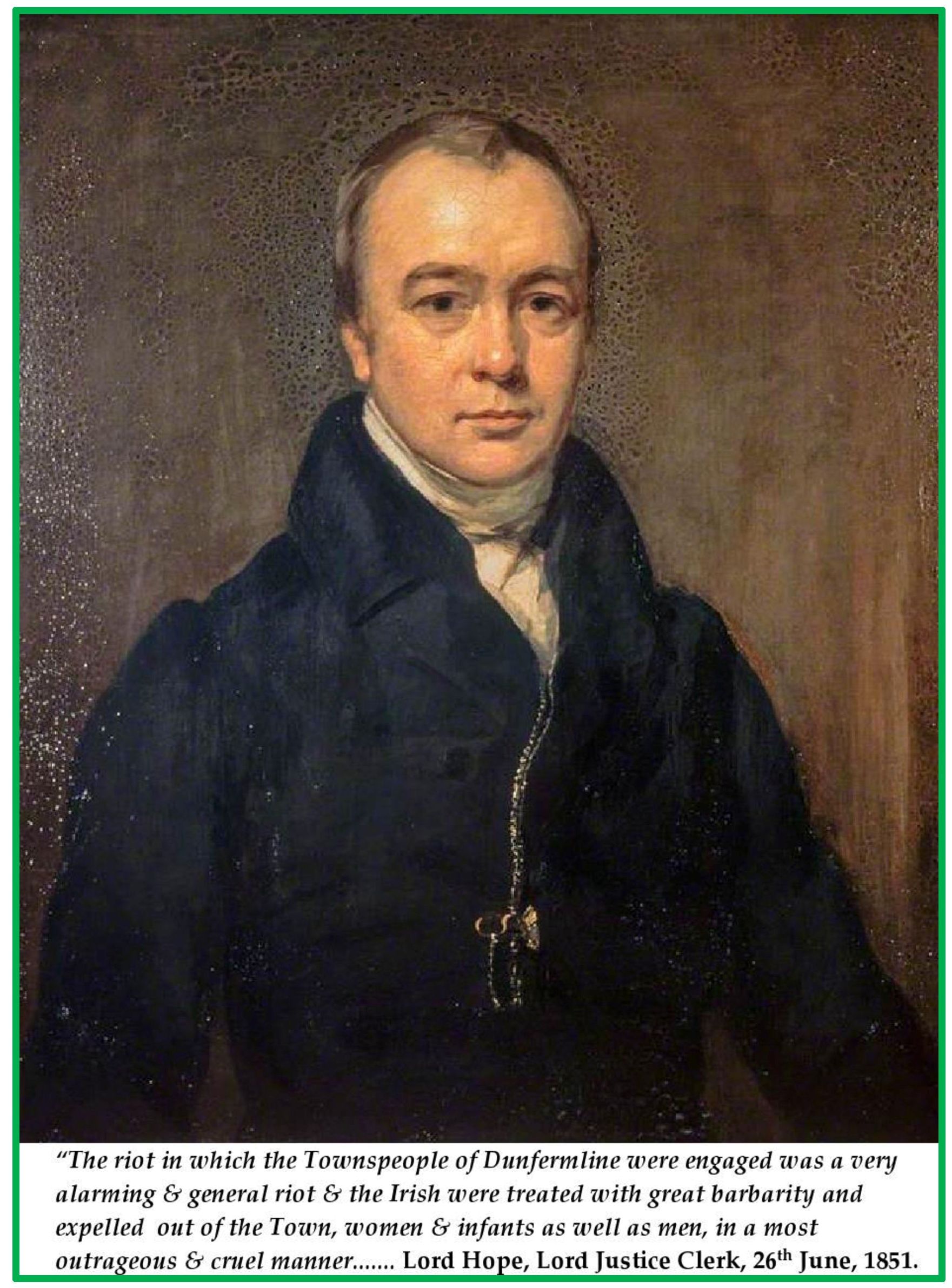

When the Lord Justice Clerk, Lord Hope, reviewed the petition along with Lord Ivory’s letter he shared none of Lord Ivory’s sentiments.

Lord Hope totally rejected Lord Ivory’s view that the twelve native rioters were carried away with the excitement of the mob and felt provoked by the Irish assaults, or that this offered some justification, or mitigation for their acts. Nor did he agree with Lords Ivory and Mackenzie’s lenient sentencing.

In rejecting the Dunfermline magistrates & others, petition for clemency for Black in the strongest possible terms Lord Hope stated:

“The riot in which the Townspeople of Dunfermline were engaged was a very alarming & general riot & the Irish were treated with great barbarity and expelled out of the Town, women & infants as well as men, in a most outrageous & cruel manner……. The Riot was regularly conceived & planned – no one therefore had any excuse who joined in it: It’s purpose was open & avowed: All that was done was executed deliberately & by great violence: The Individual acts of violence charged agt Black & His son & others to which He pleaded guilty prove very direct action & leading participation in the illegal objects & outrageous conduct of the Mob.

That the Magistrates & others may have a strong feeling agt the Irish Catholics & in favour of the Townspeople is very far from recommending in my opinion any Mitigation of this lenient Sentence.”

From Lord Hope’s Report to the Home Secretary we see for the first time mention of the Irish as being Catholics. Lord Hope’s Report

In rejecting the Magistrate and people of Dunfermline’s petition presented by Mr. J. B. Smith, MP, Lord Hope’s Report gave reasons that were simply stating the obvious, namely, that the 18 and 15 months jail sentences given to the Dunfermline natives for acts of “great barbarity” against innocent men, women and children were “extremely lenient and any mitigation of it would be very inexpedient”.

From the back page of the petition we can see the initials of Sir George Grey, the Home Secretary as evidence of his rejection of this petition by the Magistrates and other inhabitants of Dunfermline.

CLEMENCY FOR PETER COONEY?

Peter Cooney had petitioned the Home Secretary, Spencer Horatio Walpole, on the 17th of March (St. Patrick’s Day), 1852 and though he had to wait for 668 days for his decision, his wait was worthwhile, as his plea for clemency was granted.

No doubt the stated opinion of the staff at Portland Prison that Cooney merited a reduction in “consequence of his exemplary character” had a part to play in this decision. Prison Commission Records

On 27th January 1854, pursuant to Licence No 352, granted on the 14th January, and with less than half of his 7 year prison sentence served, Peter Cooney was released into the care of Josiah Clyde, a merchant in Falkirk.

Summary of the Charges, Prisons, Petitions & Clemency The Charges (Scots Law Indictments) give a lie to the myth created by the press that the Irish had planned and put into practice a mock-fight to lure innocent bystanders into an ambush. Were that the case the authorities would have been quick to charge the two Irish navvies with this nefarious plan, which would have constituted the crime of Mobbing and Rioting.

The Charges also show that the injuries as a result of assaults reported by the press were misleading, in that they concentrated on those inflicted by the Irish navvies, which they exaggerated greatly (See David Anderson below), while ignoring the vastly greater number of brutal assaults and one death suffered by the Irish rersidents.

Lord Hope’s Report to the Home Secretary reveals the true nature and causes of the mob violence was not as the newspaper’s opined, a reactionary revenge for a Saturday night affray, but rather it was a regularly conceived and planned affair, mainly about race, and (the other, unstated factor, until Lord Hope identified it) religion.

With anti-Irish and anti-RC views prevalent in Scotland at the time it’s not hard to see how a simple Saturday night drink-fuelled affray would be portrayed as an atrocity, and the two Irishmen who committed three assaults into ogres, while the numerous planned and orchestrated crimes of two or three thousand Scots native inhabitants were sanitised, explained away in the best possible light as an understandable reaction to the atrocities of the former, and, as far as their assaults were concerned, went unheralded and unpunished.

In his reasoning for rejecting the pleas of Black’s supporters, Lord Hope, the Lord Justice Clerk shared my bafflement at the light sentences given to the natives of Dunfermline who had committed so many violent crimes, as he too seemed at a loss to understand it, and refused to recommend any reduction of it. To believe their sentences were appropriate, as Lord Ivory opined, would be to accept that stealing a handkerchief from someone’s pocket or a pair of trousers from a drying green was worthy of transportation for 7-10 years, but driving a whole community out town was only worthy of 12-15 months in prison.

What Lord Hope’s report didn’t, or perhaps couldn’t fully explain, was why the most prominent burghers of Dunfermline, the civic leaders who should have exemplified law and order, felt it was their duty to bring home Alexander Black Senior, one of the leaders of the mob that had brought the town to the brink of anarchy. That is a puzzle I will attempt to unravel in the next part……

….Continued in Part Four: Why did the civic leaders of Dunfermline petition for the release of mob leader Alexander Black? + My verdict!

Post Script.

What became of them?

Reports of David Anderson’s imminent demise, then disability were greatly exaggerated. He lived a long active life in his hometown of Dysart some 24 kilometres from Dunfermline, where he continued work as a hand-loom weaver there for some years, before becoming a carter, until his death there on 20 August 1891 aged 67. Ancestry file D. Anderson

Alexander Black Senior, the man so many influential Dunfermline citizens wanted released from prison early, was later convicted of assaulting a fellow miner with a shovel and died on 14 January 1878 aged 75, as a result of being run over by a coal wagon at a Cowdenbeath pit. Ancestry file A. Black

Nothing is known of Peter Cooney (various spellings of surname make research difficult) as his trail runs cold after he was released, but unlike Black he doesn’t feature in any Criminal Kalendar entries after his release from prison. Ancestry file P. Cooney