This NOTE is pinned inside a Camphorwood Chest at my home in Dunfermline.

For some years now I had been meaning to write a note about the purchase of this camphorwood linen chest and pin it inside, but it was only when Russell Darnley, an Australian author, sent me an audio book of his entitled “Camphor Silk and Ivory” that I was prompted to get down to my task.

Hopefully this linen chest will stay in my family for a long time as it has a special place in my heart and the smell of camphor, though fading, brings back memories to me that I will share with you:

I was just 20 years old in 1965 when I completed my 5-year apprenticeship as a shipwright in HM Rosyth Dockyard, but I never collected a tradesman’s wage because I had already made arrangements to join the Clan Line Steamers Co. of Glasgow, as a ship’s-carpenter as soon as my indenture papers freed me from the dockyard.

My keenness to get out and see the world was shared by one of my workmates at Rosyth, James Keith ‘Nick’ McIntosh, who I had been at King’s Road secondary school with. Nick was an engine fitter and like me went to sea at the first opportunity and though we never sailed together he was a good mate and sometimes we were on leave at the same time and so it was that one lunchtime in late November 1967, we found ourselves drinking in Rosyth Dockyard Recreation Club.

I had moved on from being a ‘company man’ with the Clan Line, which was a strictly racist company, having White, European officers and Coloured, Asian or African crews (Lloyds hard-stamped the steel in the cabins to certify them as fit for 1 E (European) or 2-4 A (Asian) seamen) and this, and the bullshit that went such as having to wear dress uniform for meals with it didn’t sit well with me. So I had left that company and joined the British Shipping Federation ‘Pool’.

The ‘Pool’ had offices at all the major ports and was financed by British ship owners’ as a kind of Labour Exchange for seamen. The way the Pool worked was that once a sailor paid off a ship and his leave was at an end, he ‘signed on’ and was paid a weekly retainer on the basis that he was available to join a ship when a crew vacancy became available.

The rule was that a seaman got three choices of ships, but if he didn’t fancy the first two offers he had to accept the third or he was “blacked” by the owner’s union and would have difficulty going to sea again.

Nick and I, both single and living with our parents, had expended our leave as well as our money and with Christmas coming were ready for the off when Nick got a message from his mother telling him he was to phone the Grangemouth Pool.

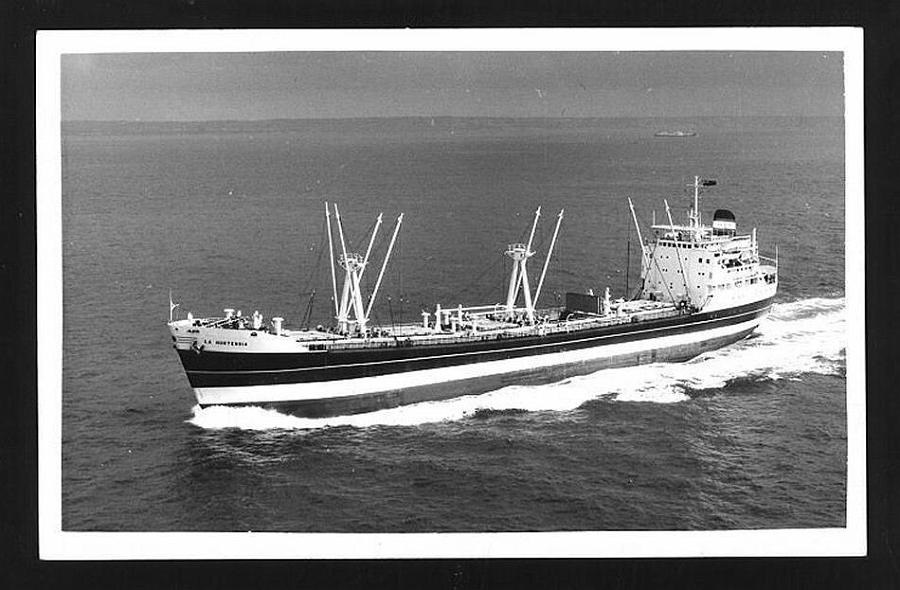

When Nick phoned he was told there was a job for a junior engineer on the M.V. La’ Hortensia, a tramp bulk carrier lying in Turkey, bound for destinations unknown and he had to fly out to Istanbul to join her the following day. We drank one or two for the road then said our goodbyes and off he went.

I missed my drinking partner, but there were always plenty of other men to spend the time with in Rosyth and the next day I was back drinking in the Dockyard Club, playing snooker and speculating on Nick’s eventual destination and when he would be home again.

I should explain that at the time the Dockyard Club, like many others, was an all-male domain with women just beginning to get their foothold into the lounge and of course the dance-hall at weekends. But the main bar area, the games room and the billiard room was strictly off limits to all but male members or visitors. Women who wanted to see their husbands (often on pay-day when hubby had decided to try his luck at the card school with the wages) didn’t get past the doorman and they even had a job to speak to them on the phone, so when a woman phoned to speak to me the bar-steward asked me (with the mouthpiece covered) “are you in Tam?” I said I was in to callers and took the phone call, which was from my foster mother, who advised me that a telegram had arrived at our house asking me to phone the Grangemouth Pool.

I phoned the Pool and they offered me a job as carpenter on the King Malcolm, a tramp going to the country we then called ‘Communist, or Red China’, the Republic of China then, was what is now known as Taiwan. This ship coincidentally belonged to Cayzer Irvine, the same group that owned the Clan Line. She was a tramp, that is, she picked up cargoes as and when required, and might be away for two years before having to pay her crew off or head for home.

MV King Malcolm (Above) leaving Cape Town harbour.

MV King Malcolm (Above) leaving Cape Town harbour.

This post wasn’t immediately attractive, but I had recently turned down one job on a Royal Fleet Auxiliary oil-tanker and if I didn’t take this offer the next offer gave me Hobson’s choice, i.e. none; so I accepted the job, comforted by the fact that I would be sailing south into the sunshine, away from the cold weather.

The next day, the 29th November 1967, found me signing on in Glasgow at the Shipping Office in the Broomielaw and when I asked for an advance in wages I wasn’t rebuffed by the company’s agent, but instead, and much to my surprise, was given a generous cash ‘sub’ on the spot. Other crewmen were treated similarly and we couldn’t believe our luck, rushing to get our gear aboard the ship which was lying at King George V Dock, Shieldhall and get into town for a bevy session before the ship sailed that evening.

The departure from Glasgow is shrouded in the mist of time and alcohol, but I remember the next morning I was late in ‘turning-to’, but nothing was said to me so I got on with my working routine, which started with me sounding the ship’s bilges for water. This involved going round the deck and at certain positions unscrewing a capped pipe that led all the way to the bilges at the bottom of the hold and dropping a measuring line down to see if the ship was taking in water.

I had dropped my sounding line down about half a dozen times when it slowly dawned on my booze-fuddled brain that the land was on the starboard side of the ship as was the sun, indicating we were heading north and not south to sunnier climes.

My routine was that when I had entered all of my ‘soundings’ in a ledger for that purpose I took them to the Mate (First Officer) on the bridge who would then give me my jobs for the day. When I did this I mentioned the fact that I understood we were sailing for China, but we seemed to be heading north. The Mate laughed and said we were indeed sailing to China, but first we had the small matter of collecting our cargo of wood pulp in Finnish Lapland!

This revelation came as a complete surprise to me and the majority of the other crewmen who, unlike me (I always packed a duffle coat and divers’ jersey in my case) had came away with no winter clothing on the basis that they soon wouldn’t need any. That morning’s ‘smoke-o’ (tea-break) was taken up by grumbling, mainly among the deck-crew that they had been conned and were likely to suffer because of the cold. One seaman had embarked with the clothes he stood in, Wrangler jeans, jacket and a t-shirt.

We quickly realised that the company had pulled a ‘fast-one’. Without actually lying the Glasgow Shipping agents hadn’t spelled out the fact that our new home was not heading directly south, round the Cape of Good Hope to China, but was slowly, at a top speed of about 12 knots, steaming towards Kemi in Finland, just 50 miles south of the Arctic Circle.

With the benefit of many years of hindsight it is apparent to me now, that what the Shipping Agent in Glasgow did then was akin to what a Travel Agent might do in selling a package holiday on the promise of a smart hotel fronted by golden sands and a blue ocean, without mentioning the fact that a sewage-works was next door and upwind of it.

The shipping company must have reckoned that a few hundred pounds in advances paid to drouthy sailors was a small price to pay to get their vessel crewed and sailing on time, with no awkward questions asked. Questions that a more sober and circumspect crew might have posed about provision of winter clothing etc. were left unsaid in our rush to the pubs. This was a misjudgement on our part, but not as big as the misjudgement the company had made as it later transpired.

The week-long voyage north to Kemi via the Pentland Firth, North Sea, Baltic Sea and Gulf of Bothnia brought colder and colder weather. Just short of our destination, the heating in the crew’s quarters, which were in the stern of the ship failed when the water filled radiator system froze solid.

The ship simply wasn’t designed for Arctic conditions such as those we experienced and the crew were unable to sleep in their accommodation, which were now steel ice-boxes. Most slept in the crew’s mess-room, which was amidships, above the engine room where the heat from the ship’s engine kept the temperature up and stopped the heating system from freezing up.

I was in comparative luxury as my single berth cabin was in the midships accommodation heated by electric fan heaters and I took in the most aged member of the crew, Leo, an old greaser from Glasgow, who slept on my day-bed.

When entering port It was my job to stand-by the anchor windlass in case we had to drop anchor in an emergency and on entering Kemi I took up station on the forecastle wrapped in my duffle-coat, underneath, which I was swathed in as much clothing as I could get on in addition to wrapping towels round my head, body and stuffing newspapers down my trouser legs. I had gloves on and carried a cup of hot coco with me. When I spilled a drop of my drink I was amazed to see it hit my boots as ice. This was cold which was different from anything I had ever experienced before, or since.

When the King Malcolm docked and the main engines were shut down, the entire ship, with the exception of a few areas amidships froze solid. Domestic water tanks/pipes froze, so toilets wouldn’t flush and there was no running water except for the galley meaning that all ablutions had to be carried out in the dockers’ portakabins ashore we were given the use of.

Our new washing facilities were in electrically heated portakabins, but the toilets were dry, a plank of wood in a hut over a hole in the ground. This hut backed on to a forest and given that there were wolves in the area I felt vulnerable and learned the knack of defecating with my hands cupped firmly around my scrotum lest a wolf fancied a sweetbread starter!

The crew at this point were in open revolt, threatening to refuse to sail the ship, and their cause was taken up by local press and TV. The Master and the Mate did their best to handle the situation by providing cold weather clothing free of charge to those who didn’t have any, which alleviated the situation somewhat.

A much bigger problem surfaced however, when it was found that the tubular steel main-mast, which supported the ship’s derricks had split open like a burst tomato. This was because over the years water had managed to get inside it, up to a depth of about 4ft from the base. The base of the mast was housed in the tween-deck and when the sub-zero temperatures had reached -40°C the expanding ice had nowhere to go and burst the ¾ inch thick x 3ft diameter mast as if it were a beer can.

The damage to the mast was a major problem that couldn’t be fixed in Kemi and we loaded our cargo of bails of wood pulp using dockside cranes and headed south for Sweden and repairs. As we left Kemi the ship ran into sea-ice about 1 or 2 inches thick; not thick enough to stop our progress, but enough to slow it and risk damage, so the services of a Kemi-based ice-breaking vessel Sampo were called on and it was a spectacular site to see this large, state of the art craft come thundering up behind us and overtake us at speed smashing a path through the ice as if it weren’t there.

Kemi-based icebreaker Sampo, which is now a tourist attraction and no longer operational.

Kemi-based icebreaker Sampo, which is now a tourist attraction and no longer operational.

Once free of the ice we sailed on and a few days later, just before Christmas, we docked in the Swedish port of Sundsvall where the whole ship’s crew were decanted into an hotel. The plight of the King Malcolm had travelled quickly, as bad news does, and again the press were interviewing the spokesmen for the crew who were still smarting from the conditions that they had endured and now they were lubricated by the beer that was available, free, by the case as room-service.

I wouldn’t want to run-down my fellow seafarers, who were mostly Scots, but they were not the most sober or steady seafarers, and I say this as being no angel myself. Being recruited on an old tramp leaving at Christmas time for destinations and duration unknown didn’t appeal to most steady, family-men types, so our lot were mostly like me, single and skint, and, unlike me, there were many who were on a final warning with the Shipping Federation due to misconduct on other ships. Let’s just say the motley crew of the King Malcolm wouldn’t have been considered as potential crewmen for the Royal Yacht Britannia and being let loose in a good hotel on Christmas day with access to unlimited drink inevitably led to chaotic scenes.

Christmas postcard sent to my girlfriend Nan from Sundsvall

Christmas postcard sent to my girlfriend Nan from Sundsvall

The brief Christmas shore leave for the crew of the King Malcolm allowed local engineering and plumbing companies to fix the ship’s heating system and water pipes, but the major problem, that of the ship’s broken main-mast, was a task too big for these local contractors and arrangements were made for the ship to dock at Kiel in Germany for this work to be carried out.

I can’t remember our departure from Sundsvall, but can remember our entry into the mouth of the Kiel Canal on Hogmanay as I spent it on the main deck of the ship fighting an aggressive greaser from Ayrshire who while drinking in the crews mess decided he didn’t like me, challenged me to a fight on deck and told me he was going to throw me over the side of the speeding vessel. I don’t consider myself a hard-case, but he had made a mistake in telling me of his goal and the prospect of going for a midnight dip in the ice cold waters of the Baltic gave me the determination and strength to knock this notion out of his head.

Once tied-up alongside at Kiel the Master decided that because of our recent grim circumstances he would allow anyone who wanted to pay-off to do so and be flown home. Names were taken and about half the crew (including my former boxing opponent) opted for this premature pay-off. Replacements were flown-out, mostly from England and once the mast was repaired we eventually set sail for China.

There were no real problems on the remainder of our outward voyage. We bunkered (took on fuel oil) at Dakar in Senegal and then continued round the Cape and up through the Indian Ocean and Malacca Straits to Singapore. More fuel was taken at Singapore and then we sailed on to Shanghai, the first of our two discharge ports in China.

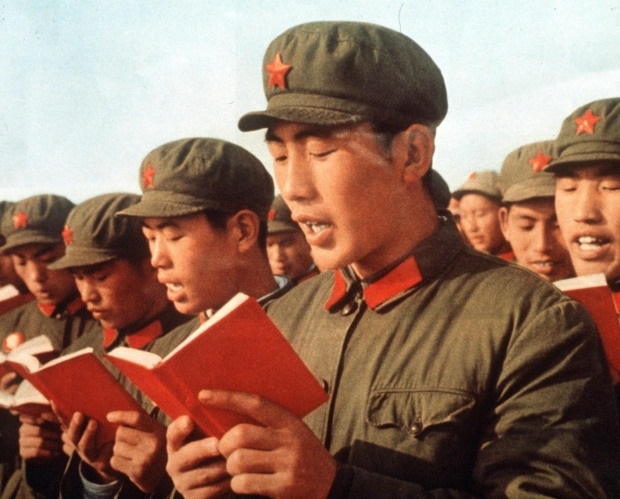

We arrived in Shanghai, which is on the Huangpu (pronounced Whang-poo) River in early April 1968 and it was a sight to behold. There was revolution in the air, even on the tugs and pilot/customs vessels that approached us as we neared the port. These vessels all bore flags of the people’s republic, which were complimented by large portraits of Chairman Mao Tse Tung and there was a musical accompaniment too, a constant blare from loudspeakers of martial type stirring music and speeches in Mandarin, which extolled (we were informed) the virtues of the Cultural Revolution as opposed to the decadence of the capitalist USA and their ‘running dogs’ = us.

It’s hard to describe the feverish atmosphere that pervaded every facet of life in Shanghai; from dawn to dusk there was a constant bombardment of noise from loudspeakers everywhere. There were also endless small meetings, sometimes as small as one at each hatch of the ship where a Red Guard leader addressed his audience of workers with readings from the little red book containing “The thoughts of Chairman Mao Tse Tung” or from newssheets. The audience took their cue from the speaker and threw their arms in the air and chanted slogans in response to the speaker at various intervals.

The Chinese people and the Red Guards didn’t involve the ship’s crew in their activities as a rule, but they did thrust Chairman Mao badges on us and of course little red books. It was considered the proper thing to accept the badges we didn’t already have, and in this manner I was given 50 or more different designs (we collected them like stamps) and one of the crew amassed 200. The badges all had one thing in common, the head of Chairman Mao.

The Chinese people and the Red Guards didn’t involve the ship’s crew in their activities as a rule, but they did thrust Chairman Mao badges on us and of course little red books. It was considered the proper thing to accept the badges we didn’t already have, and in this manner I was given 50 or more different designs (we collected them like stamps) and one of the crew amassed 200. The badges all had one thing in common, the head of Chairman Mao.

The other only other thing the Red Guards encouraged us to do was watch a parade of soldiers of the People’s Liberation Army march along the quayside where our ship was being unloaded. From the ship we also saw a humiliation session taking place whereby intellectuals, refined, dignified and obviously frightened people, were berated and made to dig trenches, to toil alongside labourers in the docks, they then they had to stand, heads bowed in humility as they got a sherricking from the shrieking cadre-leader on a soap-box.

To me, broadly speaking there seemed to be two main types of person in China at this time, those who were enthusiastic about the Cultural Revolution and those who knew that they had to appear enthusiastic. Perhaps there were a major third group, those who opposed it but they were nowhere to be seen, if they still existed at this point.

And of course there was a minor, fourth class of person, the poor peasant families who lived onboard and plied their ancient junks up and down the river, tacking against the flow or riding it, they alone seemed to have been left out of the radical purges taking place. Dressed in traditional black garb, they worked, cooked and defecated from a plank with a hole in it (like I did in Kemi), which jutted out of the stern of their timeless craft. They seemed to be the only ones unaffected by the turmoil that swept the country.

There was only one place that westerners could go to for recreation in Shanghai and that was the Friendship Store, a state-sponsored outlet for foreign seafarers, who at that time were about the only visitors to the city, apart from Albanian diplomats who were China’s sole ally at that time.

The Friendship Store was on ‘The Bund’ an area on the opposite side of the river from where our ship was berthed. The store was off limits to the local population and it sold jade ornaments and other traditional craft-work, including camphorwood chests to westerners. It was an impressive building, said to be a former embassy or bank and had a big set of steps leading up to it from the street. At the foot of these steps the state photographers took up positions late at night to take snaps of the drunken sailors falling down them at closing time.

The photos were then reproduced and posted on notice boards accompanied by scathing commentary as propaganda depicting decadent westerners. The beer on sale in Shanghai was Tsingtao, made to the same recipe and at the same brewery that the Germans had made it at in the 1930s when they had a concession in China. It was good, but the spirits, at about 25p a bottle, were wicked. They were all the same raw alcohol with a different colouring and touch of flavour to give the appearance of Rum, Whisky, Gin, Brandy or Vodka. With this cheap alcohol available the store was the scene of many a drunken session among the crew of the King Malcolm and no doubt on occasion our departure at closing time would have made suitable propaganda material for the state snappers.

There were sober moments though, and in one of these I had a superb meal in the restaurant and selected a camphorwood chest, complying with the only request my foster mother had made of me when she know my destination. Sadly at this time there were none to be had depicting truly traditional scenes, as these were considered part of a decadent past and as such, taboo, all art was now modified to show the peasants in the company of Red Guards with rifles slung over their shoulders. The best I could find was a hybrid chest showing some traditional scenes of junks on the back and sides with group details of peasants being supervised, or helped by Red Guards on the front and top. Anyway I paid about £25 for purchase and delivery to the ship.

Detail from top of chest shows Red Guard with rifle (2nd left) and far right helping peasants, 1 wearing a dǒulì, the traditional Chinese conical hat.

The front detail appears to show two Red Guards overseeing traditionally dressed peasants in the field.

When the 1-Metre long linen chest arrived at my cabin door it was encased in a padded protective coat slung from a bamboo pole and carried the 2-miles from the store by two men. When I tried to give them a few Chinese banknotes for a ‘tip’ they reacted as if they had been scalded with boiling water, jumping back and furiously shaking their heads, their hands outstretched and outspread in refusal. They were terrified to be seen to be accepting anything from the corrupt and evil westerners they had been conditioned to despise, as the consequences they might suffer if this was perceived to be the case were severe.

After Shanghai our ship had a voyage of about three days sailing to Hsingkang Port on the estuary of the Haihe River, in central eastern China about 70 miles from Beijing the city it serves. This was where we were to discharge the remainder of our cargo of wood pulp and we were told to expect delays as there was a big backlog of shipping at this port.

Our order were to anchor in the bay, off the port, and when we did, imagine my surprise when, of the 42 ships at anchor we were closest to the M.V. La’ Hortensia! Standing on the forecastle after we dropped anchor I could see Nick about half a mile away waving his arms in semaphore fashion.

Now if we had asked a bookmaker to give us odds of arriving within half a mile of each other from different starting points we would have got a million-to-one our money, but here we were. Nick had taken a more straightforward route sailing from Istanbul to Constantia in Romania where his ship loaded aluminium ingots then taking on bunkers at Dakar and Singapore en route to Hsingkang.

Nick and I managed to exchange letters via the supply boats that serviced the ships at anchor, but that was the only contact we had. He told me he was soon to be a father and was keen to get home to his girlfriend.

Neither Nick nor I knew how long our ships would be at anchor as the Chinese were very secretive about such things and European Masters were afraid to ask too many questions as they were liable to be arrested for spying. In the event my ship was taken into port first after lying at anchor for 4 weeks. The government must have needed more paper for all of the Little Red Books they were publishing! So when King Malcolm sailed for Japan to load cargo for Australia, Nick’s ship was still waiting to go in to the port. He told me later that he had to wait for two and a half months to go alongside and for most of that time his ship had no alcohol or tobacco. He said the crew were afraid to look at one another such was the strained atmosphere onboard.

While at Hsingkang I saw the scariest thing I have ever seen. About four of us were walking (staggering) back to our ship after a night in the Friendship Store (much smaller and more basic than Shanghai) and when we reached the dock security checkpoint we produced our British Seamen’s Card as normal to one of the guards on duty, but the Red Guard on the gate we entered was a mere boy of about 12. He did though have the obligatory machine gun slung over his shoulder.

One of the greasers in our group was a Scot, a squat, hairy bull of a man from Dundee, nick-named Cowboy was a troubled soul, on all sorts of medication and when performing his drunken party piece of stripping off his shirt and flexing his muscles, eyes-bulging, he presented a frightening sight, but in fact he wasn’t a threat and if challenged would burst into tears and kiss your hand.

The confrontation between the Cowboy and the Commie Kid caught us all unawares, but Cowboy went on a rant about having to present his identification to a wee laddie and as drunk as I was I saw that his theatrics had terrified the young Red Guard whose finger tightened on the trigger of his machine gun. Myself and another of the crew grabbed the Cowboy and bundled him past the young guard whose large almond eyes with chestnut pupils had transformed into round saucers with fear. I have never sobered up so fast in my life and our actions in bundling our shipmate away averted a disaster, but the next day the Cowboy dismissed his close-call out of hand, oblivious of the danger he had put himself and us in.

After discharging at Hsingkang our ship was given orders to steam to Japan where we were to load a general cargo for Australia. The first thing we did on arrival in Japan was to put ashore one of the greasers, a South African called Simon, nicknamed ‘Jack Dash’ after a militant union leader of the day. Simon had stocked up with the cheap Chinese spirits and had drank himself into such a state that when his supply ran out he got a dose of the Delerium Tremens (DTs) so bad that he had to be strapped into an Anderson Stretcher and taken ashore to hospital, with all his belongings.

The captain, who was a decent sort, wouldn’t have been sorry to see Simon paid-off sick, because he (Simon), had tried to get the Master arrested, when they were both in the close confines of a ferry across the river at Shanghai. Mischievously Simon had told Red Guards onboard that the captain was a wicked man, a US spy and an imperialist who treated his crew badly, which was untrue. Like I said the crew of the Royal Yacht they were not.

King Malcolm spent 4 or 5 weeks loading a general cargo on the Japanese coast. The length of time taken was because of the wide assortment of articles that made up the cargo. Before containerisation goods were packed into wooden crates or packing cases loaded in cargo nets and then manually stowed in the ship’s hold by dockers. We loaded everything from sewing needles to Toyota motor cars in the Japanese ports of Nagoya, Moji, Kobe, Shimonoseki, Shimizu, and Yokohama.

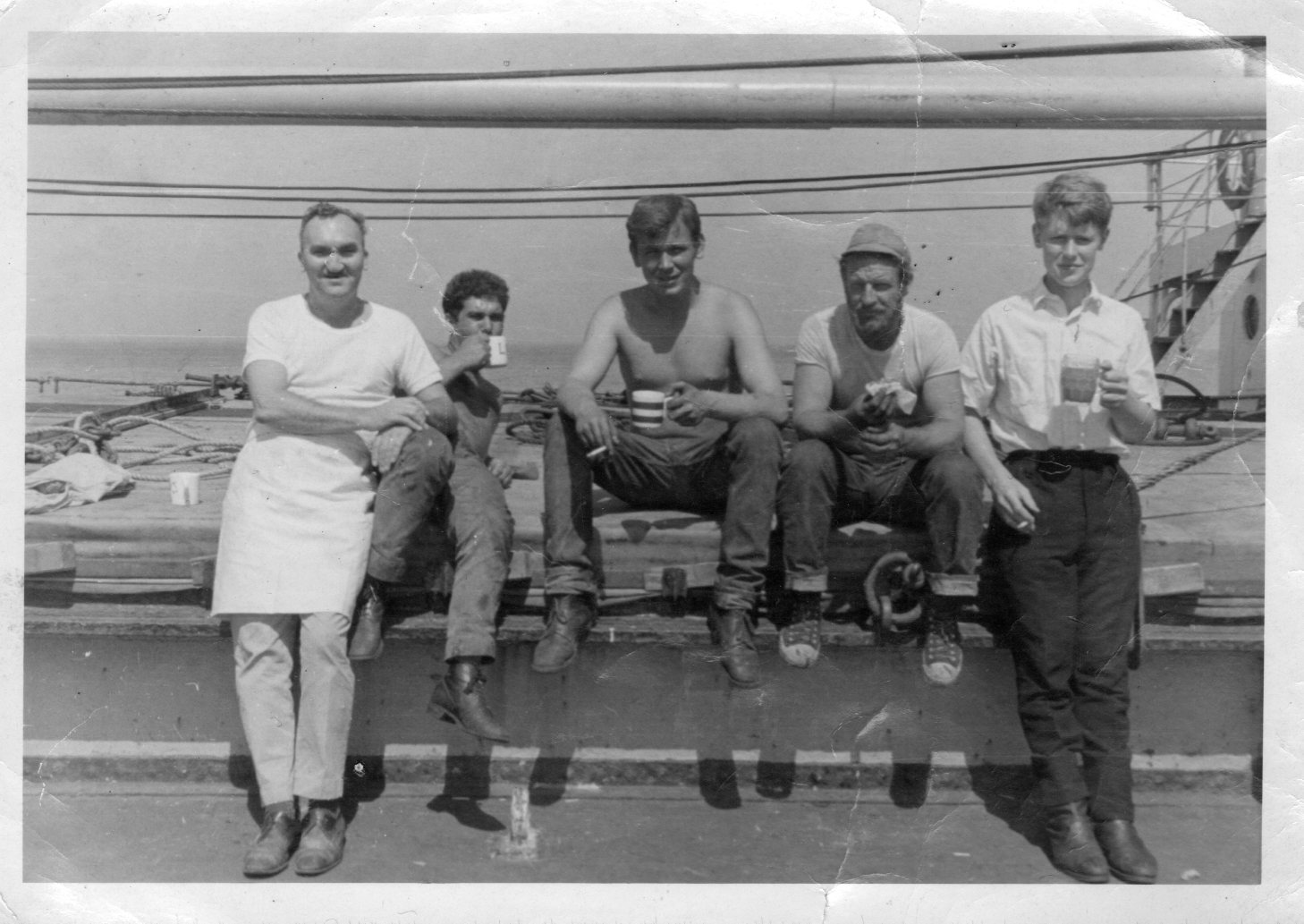

‘Smoke-o’ at 4 hatch on the Japanese coast. L to R, Tommy (cook), Len (AB), self, Jim (AB), Tony (Nav App); all English sign-ons after Kiel.

‘Smoke-o’ at 4 hatch on the Japanese coast. L to R, Tommy (cook), Len (AB), self, Jim (AB), Tony (Nav App); all English sign-ons after Kiel.

We then sailed south and discharged in the Australian ports of Brisbane, Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide. There was nothing exceptional about our time in Japan or Australia except perhaps the fact that the crew of the King Malcolm were feted on a local Sydney radio station as winning the award for the “Fight of the Week” for a brawl that had taken place in Montgomery’s Bar in Piermont. I wasn’t with the boys that night so can’t comment on the fight, but can imagine the type of thing whereby a lot of superficial damage to furniture and faces would have took place, but nothing too serious or damaging.

I liked Australia having been there about a year earlier on the MV King George an identical ship to the King Malcolm but on that occasion I had been with the Clan Line with coloured, East Pakistani (Bangladeshi) crew. I was in Melbourne when the end came to the strict licensing hours that saw dockers and office-workers take part in what was known as the ‘Six O’clock Swill’. On the night the closing hours were extended to 10pm the doors burst open at 5 and the guys all got drunk in an hour and staggered out not long after 6. They had been doing it so long their ritual couldn’t adapt to the new freedom they now enjoyed. At 7 O’clock one of the main bars in the city was almost empty.

After discharging our cargo, or what was left of it after the dockers and the crew had taken their share of the valuable items such as Yashica cameras, transistor radios, fishing reels etc we were given orders to proceed to Fiji to collect our next cargo of sugar.

At Fiji we loaded brown unrefined sugar in Suva, Lautoka, and Ellington Wharf and were back at Suva when a vital piece of the main electricity generator broke. We had to wait for 4 –weeks for a replacement part to be manufactured in Europe then flown out to Fiji.

The enforced idleness of this stay was not without its problems as we had spent our subs and had to resort to going native. This was not unusual and it was at times when money was scarce and we were counting the pennies that we got a real flavour of the ports we visited. The hotels and neon light bars were the girls hung out were off limits to the skint sailor and in Suva we went to a kava-joint, a wooden hall with corrugated iron roof, bare wooden benches and tables where chipped enamel basins full of kava with two empty coconut shells floating on the top were sold for ‘half-a-crown’ or two shillings and sixpence (12.5p) a time.

Our kava wasn’t served in any fancy dish like the above, but in a chipped enamel basin.

Our kava wasn’t served in any fancy dish like the above, but in a chipped enamel basin.

The drink had a lot of sediment and the trick was to scoop the clear liquid up with the coconut shell without disturbing it. Then drink till your face was numb!

A bunch of us had already managed to buy a cheap bottle of home-brew rum and by the end of the night I found myself outside on a grassy patch boxing with one of the seamen. A Fijian policeman in a strange dress with peaked hem stood passively watching us try to land blows. The fight was broken up, we shook hands then all went back to the ship for a final bottle of beer. I was getting settled down in my bunk when one of the lads came to my cabin and told me the guy I had been fighting was in the galley looking for a knife! I locked my cabin door and turned in and in the morning it was all forgotten.

We eventually got our replacement part which allowed us to get going again and we reached the Panama Canal without knowing where our final destination was to be.

Photo taken from the bridge showing me and a deck officer at the bow on anchor watch at Gatun Lake, Panama.

Photo taken from the bridge showing me and a deck officer at the bow on anchor watch at Gatun Lake, Panama.

Fortunately our cargo was sold to a British buyer and when we transitted the canal we sailed to Liverpool where we discharged our cargo . I paid off in Liverpool on the 9th September 1968, just 9 months and 12 days after joining.

When I arrived home I got in touch with Nick and we shared our experiences. His company, Buries Markes Ltd. hadn’t even told him the ship was going to China or he might not have joined it having already been in that troubled country (on a previous trip a Red Guard had struck Nick in the back with a rifle-butt after he tried to offer one a drink of beer). Anyway after Hsingkang his ship discharged in other Chinese ports of Ching Wang Tao, Darien, and finally Shanghai before sailing to Hong Kong where the vessel was sold to a Greek company and renamed “Lambros M. Fatsis”, and he was flown home.

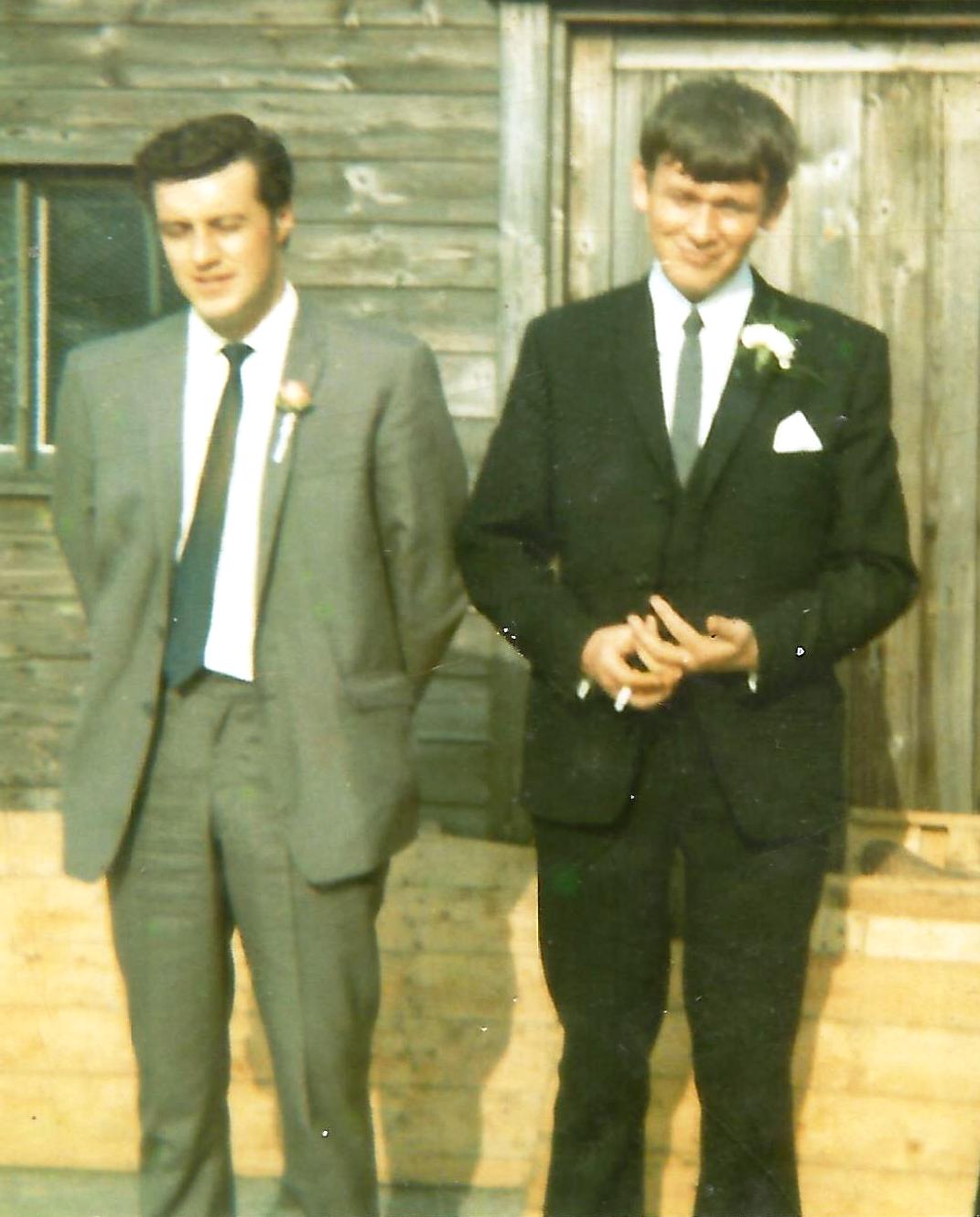

If Nick had been busy before he left home, he was busier after arriving back on Friday 7th June; just in time to see his son born on the 10th June and then he was married on the 20th June. Nick keeps in touch with Bill Gingel, one of his shipmates on the La Hortensia and when he visits Nick we share yarns about how it was in the old days.

If Nick had been busy before he left home, he was busier after arriving back on Friday 7th June; just in time to see his son born on the 10th June and then he was married on the 20th June. Nick keeps in touch with Bill Gingel, one of his shipmates on the La Hortensia and when he visits Nick we share yarns about how it was in the old days.

Nick and I and our wives dine out together on a regular basis and if we have a Tsingtao beer the talk is sure to focus on the coincidence of our (almost) meeting in Hsingkang.

Above, Nick left and me on my wedding day July 1969

I didn’t normally keep in touch with any of the men I sailed with, but I was in London soon after paying off from King Malcolm, on my way to visit Nan, my girlfriend from Dunfermline (soon to be my fiancé), who was flying out of Gatwick as an air stewardess and with time to spare I looked up some of the London crew who lived in a sailor’s home there. But even then, just days after paying off from a long voyage, they had already shipped out again. Some of our crew had no homes and just lived this nomadic existence from ship to ship with very brief spells in Britain where their hard earned cash would be spent in days.

I did bump into Leo (the old greaser who was paid off sick in Kemi) once at Celtic Park and I had a drink with him after the match. He seemed none the worse for his experiences and nor did Simon, who I bumped into in a pub Inverkeithing. Simon was at Rosyth on a Royal Fleet Auxiliary supply ship and seemed to have got over his DT’s!

The voyage on the King Malcolm was my last trip to sea. I didn’t have a long career at sea but the last 9 months had been more eventful than the previous two and a half years. When I had joined the Merchant Navy at Grangemouth Shipping Office on 14th June 1965 my medical consisted of a doctor looking at me and asking me how I felt: telling him I felt fine, he certified me as A1! Back then the large British Merchant Navy badly needed men to man the labour intensive ships, but now containerisation and foreign registration means that there are few jobs for British seamen and the ones there are will be filled by a different type of person than the ones who sailed as crew from the various Pools round the country back in the day.

Greater than the changes to our sea-power are the changes that have taken place in China, the backward, inefficient, insular and troubled country that I visited. Now China is fast on its way to becoming the number one power in the world, I reckon that 9 out of 10 manufactured items I own come from that country and as I write I am looking out of my window at the new Queensferry Crossing which is nearing completion; a bridge over a Scottish river was made in China. When I visit Shanghai on Google I can hardly believe the changes.

So I hope I have given a bit of an insight into what it was like to sail on a tramp voyage in the 1960s and if this is read in the future who knows the changes that will have taken place for those who sail the ships (will there be any sailors at all or will ships be automated completely?).

The brief note I was going to put in the camphorwood chest has now run to 14 pages, but I thought it was worth expanding on the customs of those times and of course the changes that I have seen, but the changes I have seen are as nothing to the changes that the camphor tree (lives for over a 1000 years) that provided the raw material for my chest may have stood silent witness to.

Will it have seen the Great Wall of China built only to fail to keep Genghis Khan’s marauders out?

Will it have seen the Royal Navy smash the blockade ships to force opium into Chinese ports?

Will it have seen Lord Elgin lead a joint British French force to sack the Old Summer Palace?

Will it have seen the Japanese invaders march down the Bund?

Will it have sheltered some of Chairman Mao’s or his troops on their Long March?

Will it have seen the millions purged in the Cultural Revolution marched into rural exile?

If only camphorwood could talk!

If only camphorwood could talk!

Back

Back

Side 1

Side 2

Hope you enjoyed.

Tom Minogue, 94 Victoria Terrace, 2nd August 2016.

P.S. When I visited Hsingkiang on MV King Malcolm in 1967 it only had two cargo berths and there was a huge backlog of ships anchored in the bay waiting to discharge. Now developed and called Tianjin it’s one of the largest ports in the world, covering over 120 sq kilometres, has over 200 berths for ships of all sizes, including container, cargo, and passenger vessels. The port is ranked 4th worldwide in terms of cargo traffic handling over half a billion tons per annum.