Published on: May 7, 2024 at 07:52

Andrew Carnegie Mass Murderer?

The above headline poses a question that might seem far-fetched, but it is plausible based on recorded facts, which is more than can be said of the rose-tinted, dewy-eyed, self-aggrandising rubbish accepted as fact in Carnegie’s autobiography. Perhaps what’s more revealing is something that Carnegie didn’t write about in his autobiography, namely the Johnstown Flood, which might well have been more accurately called the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club Dam Disaster.

History has generally judged Carnegie kindly, but then he was judged by an establishment that was prepared to excuse his ruthless accumulation of wealth as it was followed by his charitable dispersal of it.

Even as recently as 1993 the Carnegie Dunfermline Trustees banned a poem that criticised their founder’s work practices. LINK

It’s a fact that history is written by the winners, so it’s worth examining Carnegie’s life afresh. A Court of Historical Truth sitting in Dunfermline today and not bound by the mores of the late 19th/early 20th century will examine two charges against the Accused, Andrew Carnegie:

Firstly, that between 1862 and 31st May 1889 he did, with others, conspire to murder an unknown number of residents in Johnstown by drowning.

&

Secondly, that on 31st May 1889 he committed the Mass Murder of 2,208 men women and children [the official Government figure was 2,209, but one man listed as dead later turned up] in Johnstown, Pennsylvania.

The Case for the Prosecution in summary:

- The Accused, Andrew Carnegie was a highly-driven individual with a burning desire to succeed at any cost.

- The Accused was a man with expert knowledge of the workings and hazards of dam operations and management.

- The Accused had previous experience of the breach of the South Fork Dam, Pennsylvania, and the subsequent modifications to it that would inevitably lead, one day, to a further breach.

- The Accused knowingly facilitated, by act and/or omission, a dam failure in order to harm his main competitor’s business.

[The case for The Prosecution]

The Case for the Prosecution in detail: Carnegie was driven by ambition to succeed.

In the very few words written by Carnegie about his father William ‘Will’ Carnegie, he acknowledges that he was a broken man after the failure of his hand-loom weaving business. This meant that his mother, the daughter of another failed hand-loom weaver, had to take on the role of bread-winner. This she did by taking on menial tasks such as shoe mending and selling food she had prepared.

Late in the first half of the 19th century Dunfermline’s hand-loom weavers, once the nobility among workers, suffered when the Factory System and mechanisation made them unprofitable and unemployed.

Carnegie wrote of his father’s failure to sell his wares: “Dreadful days came when my father took the last of his webs (intricate hand-woven centre pieces for table cloths) to the great manufacturer, and I saw my mother anxiously awaiting his return, it was burnt into my heart that my father had to beg for work, it was then that I resolved to cure that when I got to be a man”

Not all hand-loom weavers accepted their fate philosophically like Will Carnegie; large mobs who didn’t railed against progress by rioting and smashing the factory looms in the town, others, like Carnegie’s ‘Uncle’ Lauder (George Lauder his mother’s brother in law), diversified and thrived.

Uncle Lauder went from being a hand-loom weaver to a blacksmith, then, became a successful shop owner and leading civic figure in Dunfermline. This man was Carnegie’s greatest influence and teacher in his formative years. A surrogate father, and until his death in 1901 a constant mentor and adviser to Carnegie, he treated him as equal to this own son George Jnr., referring affectionately to the pair as Naig and Dod.

So it was fitting that Uncle Lauder was the person to escort the Carnegie family from Dunfermline to nearby Charlestown harbour to board the steamer that would begin their quest to live the American dream.

In “The Lauder Legacy” a tribute to George Lauder, published by the Lauder College they wrote: “As Carnegie was about to be taken from the small boat to the steamer he made a rush for his Uncle Lauder and clung round his neck, crying out: “I canna leave ye! I canna leave ye!“ Eventually he was taken from Lauder by a kind sailor who lifted him onto the deck of the steamer.”

Having witnessed his father’s failure in stark contrast to Uncle Lauder’s success Carnegie had a burning desire to succeed at any cost.

The Case for the Prosecution in detail: Carnegie knew all about dams.

Most of us known damn all about dams, but are familiar with hydraulic engineering, even if we don’t know it. As children we soon learn that if we leave a tap running at full bore into a kitchen sink with the plug in it, water will eventually overflow, even if there is an overflow outlet slot or hole to prevent this happening.

As a boy Carnegie would have played in the pools and man-made watercourses or ‘Lades’ that fed the three mills which used waterwheels to power grindstones at the Heugh (steep ravine) near his Dunfermline home. Later he would learn much about the harnessing of water power from Uncle Lauder, who was raised and worked on maintenance tasks in his father’s Dunfermline snuff mill. Carnegie had hands-on experience too when he helped his ever busy mother by pumping water from the Moodie Street Well, where he would jump the queue by kicking over the buckets that others had put down to reserve their turn.

The above portrait is of the three mills within the Pittencrieff estate Dunfermline, the top mill produced flour, the middle mill meal and the bottom one snuff. The water was channelled from a dam constructed by locals to harness the ‘Tower Burn’

Carnegie’s water problems were as nothing to those of his Uncle Lauder who had lost his young wife to an illness contacted from contaminated water during childbirth. LINK This motivated Lauder to become involved in local politics and eventually, after years of political infighting, which included public petitions and a Bill to the Westminster Parliament, he convince his political opponents to back his ambitious scheme to pipe pure, clear water, into the houses of Dunfermline from Glensherup, a tributary to Glendevon Dam high in the lovely Ochil Hills, a distance of seventeen miles.

During the American Civil War, in May 1862, Carnegie wrote to his cousin Dod to say he was coming back to Dunfermline as he had been granted a three month’s leave of absence from the Pennsylvania Railroad Company (the PRR) commencing 1st July. On 28th June, Andrew, his mother and Tom Miller sailed on the screw-driven steamship Etan from New York arriving at Liverpool on the 11th of July.

The crosssing had been a troublesome one beset by storm and sighting an iceberg en route. The news that Carnegie brought with the Etna would have been well received in pro-Confederate Dunfermline where he stayed for six weeks at the house of Uncle Lauder on the High Street as it was rumoured that McClelland had abandoned his White House HQ and “Halleck’s army has been cut to pieces”. LINK

From Dunfermline Carnegie wrote: “My home, of course, was with my instructor, guide, and inspirer, George Lauder, …we had our walks and talks constantly..My dear, dear uncle, and more, much more than an uncle to me”

It is inconceivable that during this, his first visit home, the two men’s conversations did not turn to common interests, such as Lauder’s efforts, bordering on the obsessional, to pipe Dunfermline’s water supply from Glensherup reservoir, and Carnegie’s responsibility for a redundant canal feeder dam known as the PRR Western Reservoir, which had a history of leaking.

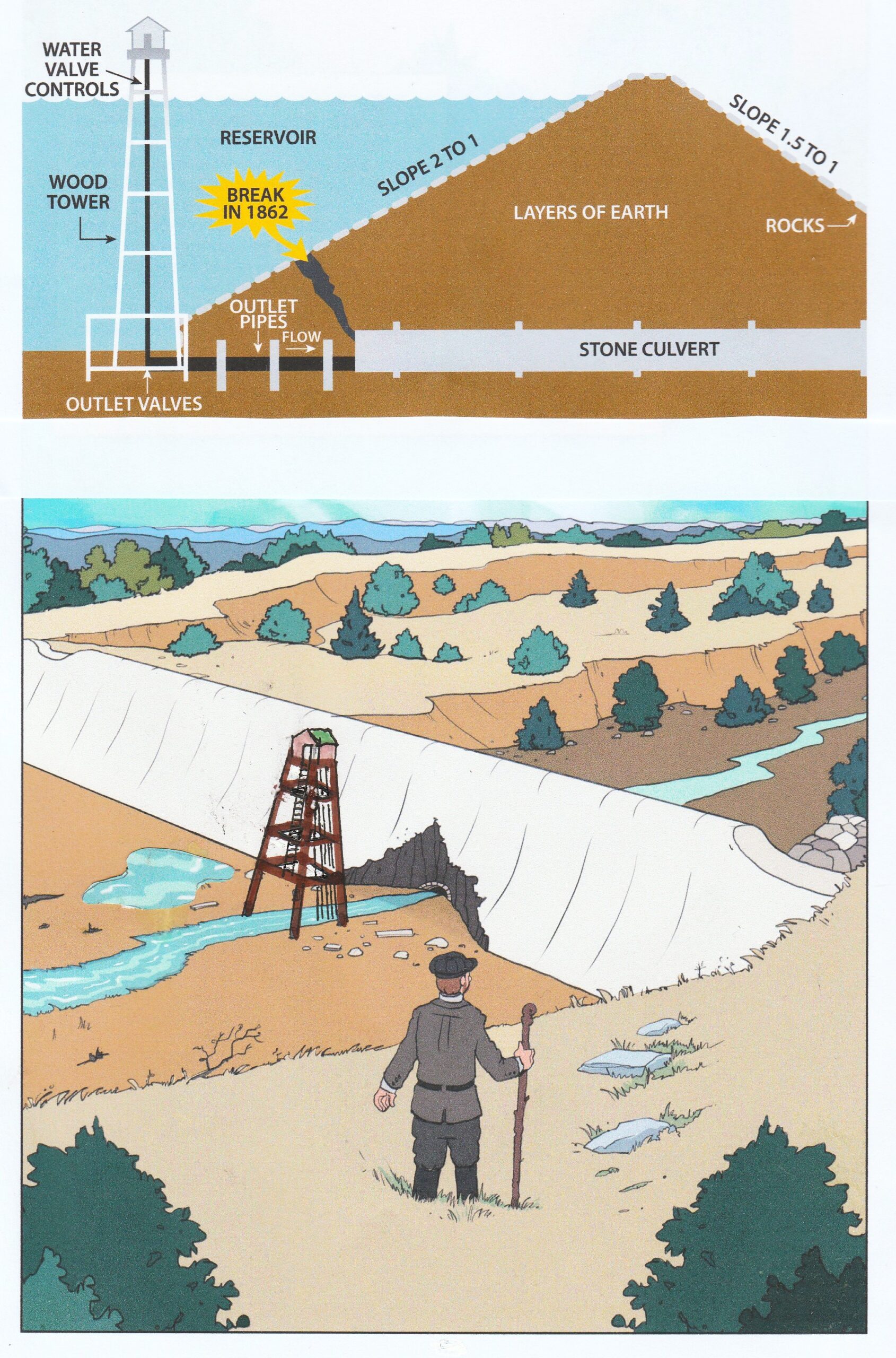

Such were the problems with the PRR’s Western Reservoir that while Carnegie was in Dunfermline in Mid July, 1862, leakage caused a partial collapse of the stone culvert that contained the drainage pipes, and later on July 26, a major collapse, happened (described in Neil M Coleman’s book as being a “triangular section of embankment about 60 m wide”). This major collapse took place soon after the PRR’s caretaker, Joseph Leckey, noticing the leakage getting worse, rowed out to the control tower and opened the 5 discharge valves to lower the level of the lake. Leckey then rode to the PRR station at Wilmore and had the telegraph operator there send a telegram warning Johnstown station of a possible flood. Soon after the warning was sent the dam failed and the lake emptied over the course of that day carrying off a house, a sawmill, and damaging the PRR’s track at Johnstown.

Carnegie would have certainly have been advised by letter of the first break in the dam (possibly the second breach too) by his Personal Secretary and brother Tom as well as his best friend and assistant at PRR Robert Pitcairn. This news would have taken about two weeks to reach Dunfermline so would have been discussed in detail at the High Street between host and guest, and if Carnegie did harbour notions in developing the PRR reservoir at South Fork at a future date, he was speaking to a man who knew a thing or two about dams. By October Carnegie was back at work in his Outer Depot office in Pittsburgh at which time he could see the damage to his reservoir for himself.

The top diagram shows the July 1862 break in the dam which emptied it while Carnegie was in Dunfermline; the lower portrait is how it would have looked to Carnegie when visited it on his return to work in October.

The top diagram shows the July 1862 break in the dam which emptied it while Carnegie was in Dunfermline; the lower portrait is how it would have looked to Carnegie when visited it on his return to work in October.

In later years, Carnegie, aware of Uncle Lauder’s wish for all boys to be given the benefit of a technical education financed and named a technical college after him. Carnegie witnessed The Lauder Technical College, Dunfermline, opening on 10 October 1889, performed by Uncle Lauder with a solid gold key. On the 100th anniversary of the college a 206 page book entitled: “The Lauder Legacy” was published by the college, within which pages 30 to 33 deal with Lauder’s successful campaign to bring clean water to Dunfermline.

George Lauder Snr. had no small opinion of his talents and as well as being a prominent businessman, politician, School Board Trustee etc., in June 1851 he signed a petition (about which, more later) as George Lauder, ‘Inventor’, a title he claimed for his practical problem solving ability in mechanical matters. This talent seems to have been inherited by his son, George Jnr. who, with the advantages of education his father didn’t have, went to university, gained a degree in engineering and patented several significant inventions of steel making equipment.

The Case for the Prosecution in detail: Carnegie knew the South Fork dam would breach, again.

Carnegie got his first job in Allegheny as a bobbin boy with a wage of $1.20 a week, then while stoking a boiler in a bobbin factory the owner said he needed clerical work done and Carnegie jumped at this opportunity to better himself. Then by chance Carnegie heard of a vacancy for a messenger in the Pittsburgh office of the O’Rielly Telegraph Co., and was taken on there. Once established with O’Rielly Carnegie was asked to recommend a boy for another vacancy and he jumped at the chance to name his best friend, and fellow Scot from his street in Allegheny, Robert “Bobby” Pitcairn.

Carnegie’s meteoric career path is well documented from when, as a 17 year old telegrapher, he caught the eye of Tom Scott the Superintendant of the Western Division of the Pennsylvania Raiload Company (PRR), who made him his secretary. Then, when Scott was promoted to Vice President in 1859, a position that meant him moving from Altoona to Pittsburgh, Andrew, aged 24, was appointed by Scott to his former position as Superintendant of the Western Division. One of the first things Carnegie did, after writing home to Uncle Lauder to tell him this latest news, was to hire his young brother Tom as his secretary and also bring his best friend in the USA, Bobby Pitcairn, into the PRR.

Just as Tom Scott had anointed Carnegie as his successor, when Carnegie left the PRR to branch out on his own as a steelmaker, he gifted his post and responsibility for the dam at South Fork to his best boyhood friend in the USA, Bobby Pitcairn. It’s impossible to emphasise just how powerful the PRR was in the USA at this time, but suffice to say it had a budget that dwarfed most countries in the world.

In the summer of 1873 Uncle Lauder and his wife spent two weeks as guests of the now wealthy Carnegie at Cresson, a PRR resort town with health springs high in the Alleghenies. As Carnegie had spent that full season (June-October) at his cottage there, it seems very likely that he and his hydraulic-engineering-fixated uncle would view the former Pennsylvania Canal Dam, which had failed (leaving a large hole 60 feet wide in the central area at the base) while he was staying with Lauder in Dunfermline, as it was only 12 miles away from Cresson. The dam was now Robert Pitcairn’s responsibility and was easily accessible by rail to Johnstown, then a 2 mile journey by horseback or carriage, and if the two men didn’t visit it they would surely have discussed its very obvious deficiencies. If they did, this time they would have had the benefit of advice from a fully qualified Master of Engineering, George Lauder Jnr., who Carnegie had consulted that same year on, the definition of the “modulus of elasticity” a technical term in the steelmaking process, which the young Lauder had elucidated for him, prompting Carnegie to offer him a job.

Soon after Uncle Lauder’s visit, in 1875, the dam was sold to a former PRR man turned politician and Congressional candidate John Reilly, then, in 1879 to Benjamin Ruff for $2,000. Ruff floated the dam as part of a leisure venture on 15 November in Allegheny County (an illegal act as the business was in Cambria County) as the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club of Pittsburgh (the Club) with 15 shares, of which Benjamin Ruff had four and his friend Henry Clay Frick 3. It seems more than likely that Carnegie either personally or through a nominee would have bought 1 of the remaining shares to give him, his business partner Henry Frick and his friend Benjamin Ruff a combined majority shareholding. The latter assumption cannot be verified as 73 pages from the Club’s records were removed after 1889 and all records mysteriously disappeared in 1910.

Soon after Uncle Lauder’s visit, in 1875, the dam was sold to a former PRR man turned politician and Congressional candidate John Reilly, then, in 1879 to Benjamin Ruff for $2,000. Ruff floated the dam as part of a leisure venture on 15 November in Allegheny County (an illegal act as the business was in Cambria County) as the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club of Pittsburgh (the Club) with 15 shares, of which Benjamin Ruff had four and his friend Henry Clay Frick 3. It seems more than likely that Carnegie either personally or through a nominee would have bought 1 of the remaining shares to give him, his business partner Henry Frick and his friend Benjamin Ruff a combined majority shareholding. The latter assumption cannot be verified as 73 pages from the Club’s records were removed after 1889 and all records mysteriously disappeared in 1910.

Benjamin Ruff began modifications to the dam for the Club 5 months before he officially owned it between early 1879 and 1880. News of the modifications to the dam to make a fishing and boating lake were of interest to the former owners the PRR as they stood to have their station and railway at Johnstown damaged if there were a repeat of the failure of July 26, 1862, which “washed away a few rods (1 rod = 16.5 feet) of the track at Johnstown.” causing the cancellation of the morning train from the East.

Robert Pitcairn was the Superintendent responsible for the safety of the PRR’s Johnstown station and railways and no doubt mindful of the previous disaster there, when a wooden platform collapsed causing 13 deaths, he ordered his engineer Superintendent Robert L. Halliday to inspect the Club’s dam and report back to him. Halliday’s report was clear in stating that the modifications made to the dam rendered it unsafe.

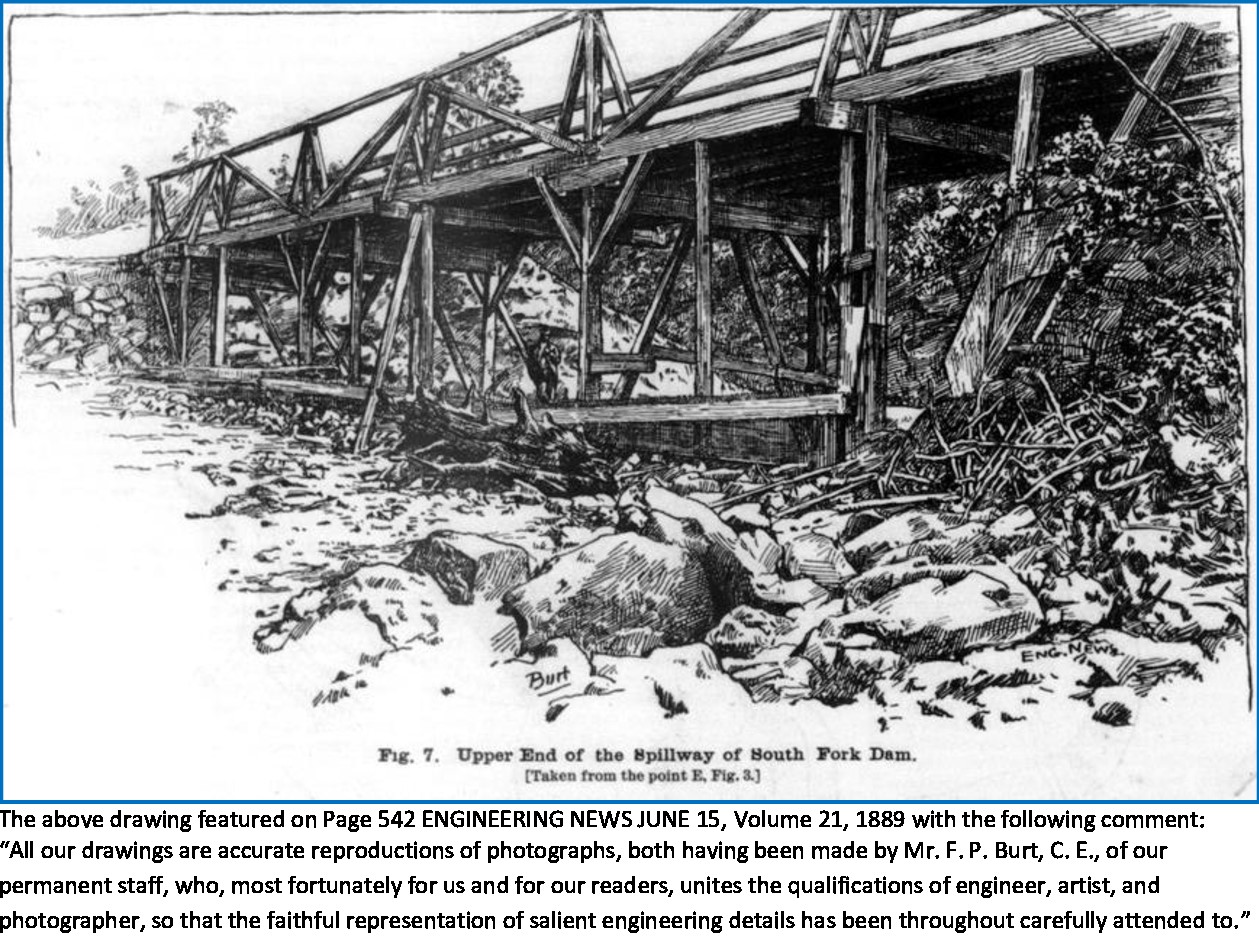

It wouldn’t take a qualified hydraulic engineer to identify the flaws in the modifications that the Club made to the dam. The earthen dam had been originally designed with three major safety devices to prevent overflow washing away its earthen body. Firstly it had 5 valve-operated, 24 inch inside diameter discharge pipes to lower water levels, then, there were two spillways, a major and an auxiliary one, cut into the bedrock to prevent overflow onto the earthen face.

The Club, under the supervision of the President, the non-qualified Benjamin Ruff removed the discharge pipes, filled the hole in the body with random earth and rubble and lowered the dam height to allow carriages to cross it, thereby removing the auxiliary slipway as a result. A detailed study by Neil M. Coleman in his book “Johnstown Flood of 1889 – Power Over Truth and The Science Behind the Disaster” states: “The club workers and officers never understood that the changes they made eliminated the auxiliary spillways and cut the safe discharge of the dam in half. That is the tragic consequence of not hiring a qualified engineer to consult on the project. The dam was now doomed”.

As if the lessening of spill capacity was not sufficiently alarming to anyone with half a brain there were other faults in the modifications carried out by Benjamin Ruff which lessened the integrity of the dam further. Without the supervision of qualified engineers, 50 unskilled workers had used random earth infill and straw (not sealed with puddling clay) to fill the 60 foot wide breach at the bottom centre of the dam left by the 1862 failure, which after settling left a dip in the road at the crest of the dam. The deficient repairs and the resultant leaks caused great concern with Johnstown steel magnate Daniel J. Morrell, so much that he had his own engineer, John Fulton carry out a survey, which resulted in a report that raised serious concerns about the integrity of the dam. Having witnessed the haphazard dumping of fill into the 1862 breach Fulton wrote to Morrell, “It did not appear to me that this work was being done in a careful and substantial manner, or with the care demanded in a large structure of this kind.”

Noting the missing discharge pipes Fulton stated: “When the full head of sixty feet is reached,” “it appears to me to be only a question of time until the former cutting [breach] is repeated. Should this break be made during a season of flood, it is evident that considerable damage would ensue along the line of the Conemaugh.”

Fulton concluded that the dam should be rebuilt properly with both a new discharge pipe and large, heavy riprap on its downstream face to prevent it being washed away in the advent of the lake topping the crest. Fulton’s report so alarmed Daniel Morrell that he forwarded it straight to Club President Benjamin Ruff, who made great play of the fact that Fulton had misnamed the club (a tactic rogues use similar to a straw man argument to deflect attention from the salient points), and dismissed it out of hand with the statement: “You and your people are in no danger from our enterprise”. In fact Fulton was soon proved right in his assessment, as in 1881, shortly after the modifications were completed a leak occurred that caused Ruff to call in an engineer to supervise urgent repair work.

History would prove that Morrell, with his steel works situated downstream of the dam, had good cause to fear danger from a break in the Club’s dam, a danger he was unable to remedy as he died two years before the dam broke.

In addition to the overflow deficiencies and slipshod rebuilding highlighted by Morrell, the club had fitted a fish screen at the spillway to stop their stocked bass/trout escaping. A wooden bridge to allow carriages to cross at the same spot had wooden support legs, which acting in tandem with the fish screen formed an obstruction to the smooth flow of water, making it a choke point where branches, reeds etc., were snagged.

Returning to the kitchen sink analogy (above), imagine the overflow slot or hole has now been partially taped over and a piece of mesh placed over the remaining open portion, the sink has been filled with tea leaves and to prevent emergency draining the drain plug removed and the plug-hole filled with concrete.

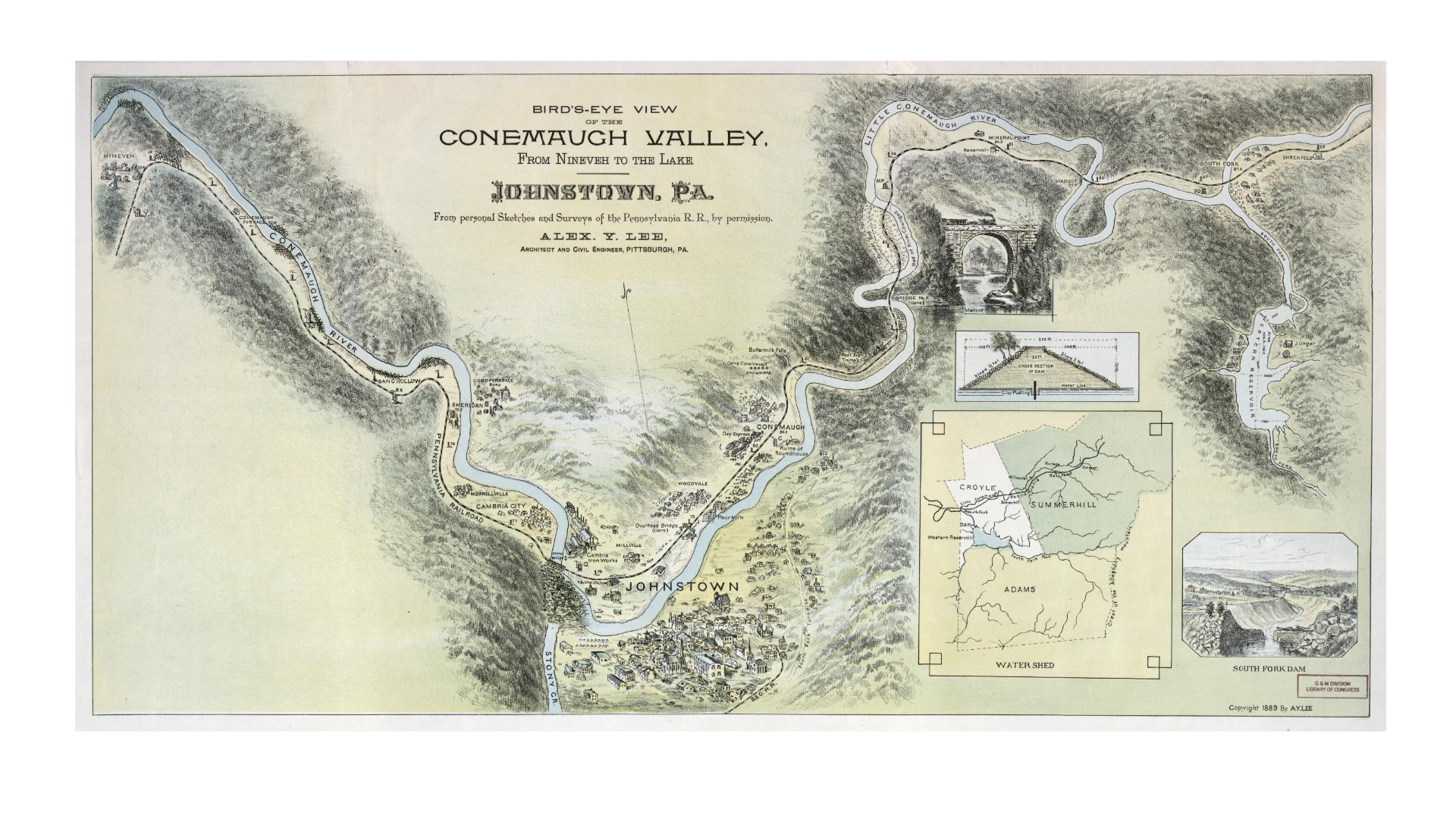

The deficiencies in the rebuilding and modification of the dam as well as the regularly reported leaks from it were common knowledge and caused much speculation about a dam failure among the citizens of Johnstown, and one, The Rev. G. W. Brown, pastor of the South Fork United Brethren Church, went to investigate and later wrote: ” The lake was a little over two miles south of our village, and, by the water course, fifteen miles from Johnstown. It covered 750 acres of ground, and had an average depth of over 30 feet. Having heard the rumor that the reservoir was leaking, I went up to see for myself. It then wanted 10 minutes of 3 o’clock in the after-noon of Friday, May 31st. When I approached, the water was running over the breast of the dam to the depth of about a foot. The first break in the earthen surface made a few minutes later was large enough to admit the passage of a train of cars. When I witnessed that, I exclaimed, ‘ God have mercy on the people below,’ but I did not then suppose that the destruction of the lake would be attended by so great loss of human life.”

The failure of the dam on 31 May 1889 was as many had predicted, but few had figured just how deadly it would be. To give some idea of the extent of the flood it is recommended that readers watch this 4 minute video.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tMc9kP9q-d8

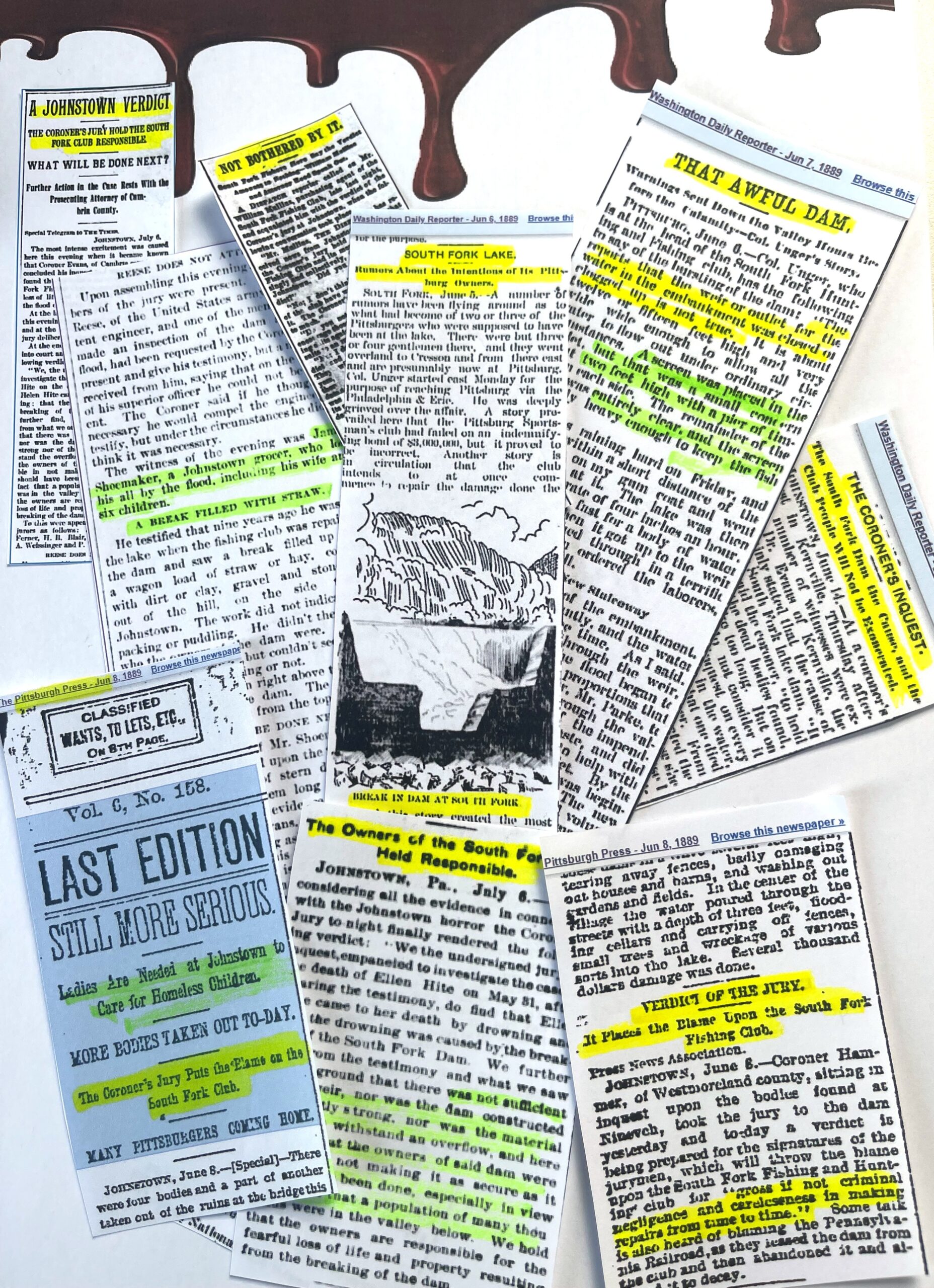

Given the magnitude of the disaster an inquest was quickly convened. Because of the large number of fatalities from the deluge it was decided that a test case on one death, that of Ellen Hite, be heard on June 14 by Cumbria County Coroner’s Court, at Kernville, Johnstown. It came as no surprise that on July 6 1889, after hearing evidence of witnesses, the jury spokesman read out the following statement: “We, the undersigned jury of inquest, empanelled to investigate the cause of the death of Ellen Hite, on the day of May 31, after hearing testimony, do find that Ellen Hite came to death from drowning, and that the drowning was caused by the breaking of the South Fork dam. We further find from the testimony and what we saw on the ground, there was not sufficient waste weir, nor was the dam constructed sufficiently strong, nor the proper material to withstand the overflow, and hence we find that the owners of said dam were culpable in not making it as secure as It should have been done, especially in view of the fact that a population of many thousands were in the valley below, and hold that the owners are responsible for the fearful loss of life and property resulting from the breaking of the dam. Witness our hands and seal July 6, 1889…

The Case for the Prosecution in detail: Carnegie knowingly facilitated a dam failure to harm a competitor.

The verdict of the jury in the Cambria Coroners’ Court brought the members of the Club into the limelight. Their immediate comments after the flood were high-handed and defensive:

June 6 – Colonel Unger (President after Ruff died), “The reports that the weir or outlet for the water in the embankment was closed or clogged up is not true” “The dam, as is known was built by the state [1839 to 1853]. We did not increase the height, but simply repaired the wall,”

June 7 – William Mullins on did he expect the Coroners’ verdict that the members were collectively responsible: “No; I don’t think any of the members of the club have worried thinking about it. The Coroners’ verdict doesn’t amount to much.”

June 11- James H. Reed, “There’s nothing in it” in response to reports that the club would hold a meeting “We don’t feel called on to hold a meeting, because the accident took place as we consider that the calamity happened through no negligence on our part,”

Carnegie was at the Paris Universal Exposition to see the Eiffel Tower at the time of the disaster and together with other US citizens sent a message of sympathy from the American Embassy, without mentioning his knowledge of the dam or membership of the Club.

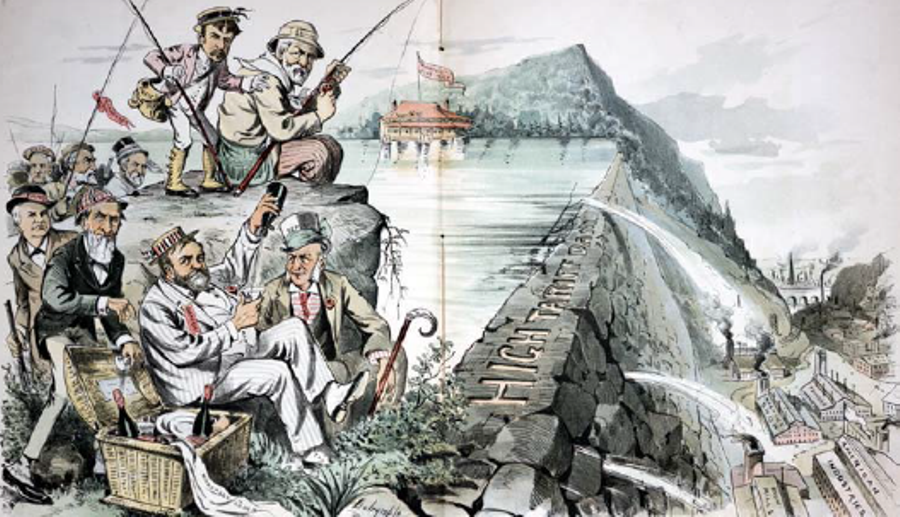

The public and the press picked up on the arrogance of the bosses club at South Fork and it was accurately depicted in the cartoon, “The Republican Monopoly Pleasure Club and its Dangerous Dam”, which was published in Puck on June 12, 1889:-

The cartoon showed Carnegie pouring Champagne surrounded by Henry Frick and other members of the club atop the leaking dam with Johnstown’s industries below, but despite the fact that it was common knowledge that Carnegie was the most prominent member of the Cub he never commented on his membership of it or of the dam’s previous failure while under his stewardship.

The cartoon showed Carnegie pouring Champagne surrounded by Henry Frick and other members of the club atop the leaking dam with Johnstown’s industries below, but despite the fact that it was common knowledge that Carnegie was the most prominent member of the Cub he never commented on his membership of it or of the dam’s previous failure while under his stewardship.

Collectively the members stood to be ruined by lawsuits if the findings of the Cambria Coroners’ jury regarding their reckless repair and maintenance of the dam were accepted in court. However the Club’s members had a reprieve in that the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) had met in New York just five days after the disaster and instigated an investigation into the reasons for the dam failure, which, in effect stymied any court actions until their findings were published.

The ASCE Committee consisted of Max Joseph Becker as Chair and a panel of three other civil engineers with vast experience in hydraulic engineering, unlike Becker, who was a railroad engineer with none, but Becker would have the job of compiling the final report and could emphasise the findings he agreed with and minimise or lessen the parts he disagreed with. At the time of the ASCE investigation Becker was employed as the Chief Engineer of the Chicago, St Louis and Pittsburgh Railway. His job involved coordinating train movements with other companies, the main one being the all powerful PRR, where Carnegie’s best friend Robert Pitcairn, a member of the Club, was the all-powerful Superintendant.

A preliminary ASCE report stated that there was no doubt the disaster would not have happened if the dam had adequate spillway capacity. The final report was given to Max Joseph Becker, the President of the ASCE on 15 Jan 1890, but was then sealed and not given to the members for seven months, and only then after Becker retired. The new ASCE President, William Shin (a former managing partner of Carnegie’s) continued with this secrecy and only made the report public two years after the disaster.

The architect of the dam rebuilding and modifications for the Club, Benjamin Ruff, who would have normally been the main witness to the ASCE inquiry had died two years before the disaster, so this role was filled by Robert Pitcairn who gave evidence in his role as Superintendent of the Western Division of the PRR, and a young engineer, John G. Parke (who had previously worked under Pitcairn at the PRR), employed by the Club to carry out sewage works on the cottages there. Pitcairn stated to the inquiry that he, like Morrell had doubts about the dam’s repairs and modifications and had sent his engineer, Robert L. Halliday, Superintendent of the Lewiston and Sudbury Division of the PRR to inspect the dam during rebuilding and he reported back that he found it unsafe, but Pitcairn couldn’t find his report.

The final, published ASCE report was a contradiction in terms saying in effect that the lack of spillway capacity caused the disaster (from the 3 hydraulic experts input?), but even with the additional capacity of the spillway and the 5 discharge pipes that were removed, the Conemaugh Dam, and many like it in existence in the USA, may have failed under similar extreme weather conditions, so it was in effect and Act of God (Editor Becker’s input?).

Those bereaved relatives who may have hoped to claim damages had waited for two years only to hear this parody of a decision from the ASCE. Having endured the tragedy of losing loved ones they must have been devastated afresh with such an ambiguous statement, which would give comfort only to defence lawyers.

The establishment had already placed hurdles in the way of justice by ruling that damages claims must be heard in the place where the club had been (illegally) incorporated, Pittsburgh, capital of Allegheny County, far away from Cambria County, the site of the dam/Johnstown and where one Coroners’ Court had already sat. The potential for malign influence of jurors in Pittsburgh, a city where most of the powerful members of the Club came from, and were influential in, was obvious; steelworkers and railroad workers would soon be out of a job if they went against their bosses.

Added further to the bereaved relatives’ woes was the fact that the ownership of cottages and rooms at Club was unclear as the records were incomplete due to the fact that 73 pages had been inexplicably removed from the Club’s bound record book. There was also the anomaly whereby the rebuilding of the dam by Benjamin Ruff’s men had began five months before the Club owned the dam, which cast doubt as to who was liable; John Reilly the previous owner, or the late Benjamin Ruff and Henry Frick. In short the bosses had got away Scot-free with murder.

But a Court of Historical Truth sitting in Dunfermline in 2024 can evaluate the facts with the benefit of hindsight, and without pressure from the rich and powerful in Pittsburgh. Let us start by looking at the members of the Club and see who stood to benefit from the dam’s failure and who would suffer.

Who Gains and Who Loses?

The Clubs’ limited membership was quintessentially White Anglo-Saxon Protestant male elite, composed of all of Pittsburgh’s movers and shakers, most of who were of Ulster/Scots or Scottish ethnicity of whom Andrew Carnegie was the pre-eminent one, followed closely by Henry Clay Frick. Most of the members worked for, or were associated with Carnegie, and like him many were members of the Duquesne Club in Pittsburgh who only frequented the clear cool air of South Fork in the summer months to escape the city’s hot, smoky air.

An exception to the above rule was Daniel Johnson Morrell, a Quaker and resident of Johnstown, who had joined the Club so that he could observe the stewardship of the dam from the inside. The dam had in the past acted like a proverbial Sword of Damocles, hanging over the valley where his company, the Cambria Iron Company, the biggest in the USA was located. Daniel Morrell was so convinced by his engineers who had predicted a breach in the dam that he offered to pay for proper repairs to the dam, including fitting discharge pipes to allow the water level to be lowered, from his own funds, but this offer was rejected by Club President Benjamin Ruff, with a statement that turned out to be so wrong: “You and your people are in no danger from our enterprise”.

Most people associate Carnegie as the father, and Pittsburgh the home, of US steel, but to put Morrell’s Cambria Iron Company in context, it was bigger than any in Pittsburgh and was producing thousands of tons of pig iron in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, when Carnegie was fetching pails of water for his mother in Dunfermline, Fife.

For a man who didn’t accept second best Carnegie must have envied Morrell’s works on summer evenings as he sat on the veranda of his cottage, or strolled along the Club’s grounds overlooking Johnstown, from where he could clearly see the glow from the Cambria mill furnaces paint a roseate hue on the clouds above. But Carnegie knew that unlike his steel mills at Braddock and Homestead 40 miles away on the Monongahela River, the Cambria mills were hostage to the weather and a faulty dam, and was an accident just waiting to happen.

The evidence suggests that a man with even a basic knowledge of the dam reconstruction could count on a breach causing flood damage as it did in 1862. Carnegie, as Superintendent of the Western Division of PRR, had stewardship of the dam then, and first-hand knowledge of the slipshod reconstruction since then, and advised by the Lauders, Frick and Pitcairn knew a repeat of that breach was inevitable. Such an event would be a body blow to the Cambria Iron Company, which would put them out of action for a while and allow Carnegie’s company to take the number one spot as the world’s biggest iron and steel producer.

It’s not as if Carnegie didn’t want to weaken Cambria, he did. In 1873 Carnegie he had enticed their best manager Captain Bill Jones to work for him at Braddock by promising him much and eventually paying him a salary of $50,000 a year, at that time equal to that of the President of the USA. Jones also enticed some of Morrell’s best men to Braddock to work with him. Did Carnegie hope a dam breach would weaken Cambria further by quenching their furnaces and closing the mills for months?

However, unlike the events during Carnegie’s stewardship, that is, the partial breach in mid-July 1862 that preceded the full breach on July 28, which over half a day had drained half-full reservoir (with only about 45 feet of water in it), causing only a large hole in the dam wall, this time the water level topped the crest (original height of 72 feet minus 3 for road widening = 69 feet) washed away the outer, unprotected layer of the earthen dam, and led to its total destruction in 10 minutes.

The sudden failure of the dam sent twenty million tons of water crashing down the valley destroying everything in its path and killing several thousand souls in the process.

“The Johnstown flood was not an act of God or nature. It was brought by human failure, human shortsightedness and selfishness.” – Historian David McCullough

“The Johnstown flood was not an act of God or nature. It was brought by human failure, human shortsightedness and selfishness.” – Historian David McCullough

In strictly business terms the beneficiaries of the dam failure were Carnegie Steel and the Pittsburgh/Duquesne-club clique, the losers, the Cambria Iron and Steel Company and the people of Johnstown.

In order to reach a verdict on the guilt or innocence of Andrew Carnegie it is necessary to examine the character of those closest to him and finally of the man himself.

Cast of Characters and The Character of The Cast.

Henry Clay Frick was a business partner of Carnegie since 1882, whom together with his friend Benjamin Ruff, had formed the Club. His anti-union stance, endorsed by Carnegie, caused a strike at Carnegie’s Homestead steel mill, which led to the infamous Homestead battle in July 1892, when Frick locked out the workforce and brought in armed Pinkertons to protect strike breakers, resulting in at least ten men being killed and sixty wounded. The same month, Frick himself was shot in an attempt on his life by a strike sympathiser, about which he cabled his mother and Carnegie stating: “Was twice shot, but not dangerously.”

Frick bore the brunt of the criticism for the “Battle of Homestead”, but it wasn’t solely his idea and was part of a pre-planned and previously used tactic at Braddock, devised by Carnegie, to break the workers union. Carnegie, knowing that bringing armed Pinkertons in to enforce the lockout of union workers and allow strike breakers to work the mill would cause bloodshed and deaths, made himself scarce by holidaying in remote spot on Rannoch Moor in Scotland 20 miles from the nearest telegraph office. When news of the deaths at Homestead broke he refused to respond to any press questions.

Later, in 1900, Frick and Carnegie had a very acrimonious fall out when Frick sued him and this enmity lasted a lifetime. When Carnegie was on his death bed he wished to make amends with his former partner before they met their maker and he sent his personal secretary James Bridge to Frick’s house with a letter to that effect. Frick read the letter, crumpled it up and tossed it back at Bridge saying “Yes, you can tell Carnegie I’ll meet him, tell him I’ll see him in Hell, where we both are going.” Frick knew the evil that he had done and was unapologetic about it, but he also knew that Carnegie was a hypocrite who believed that on judgement day in the eyes of God his charitable works would balance the books for the deaths and misery he had caused in his lifetime.

George Lauder Snr., “Uncle Lauder” Was a man who, like Carnegie, is looked on kindly by the history books. His many achievements in political campaigns for citizens’/workers’ rights, for bringing clean water, electricity and further education to Dunfermline deify him in his home town, but recently another altogether different side of George Lauder has been exposed.

In 1850, fired by anti-Irish and anti-Catholic sentiment among the local weavers and colliers an organised program by a Dunfermline mob numbering 2-3 thousand (out of the town’s 10 thousand population) systematically and with great violence drove all Irish from the town five miles south to the county boundary and were only stopped by a troop of mounted soldiers. Many Irish were injured and one died, for which 12 of the mob were jailed. George Lauder and other influential men (including Carnegie’s Uncle Tom Morrison) petitioned the Lord Justice Clerk to free Alexander Black, one of the mob leaders. Their petition was rejected by the Lord Justice Clerk who stated: “The riot in which the Townspeople of Dunfermline were engaged was a very alarming & general riot & the Irish were treated with great barbarity and expelled out of the Town, women & infants as well as men, in a most outrageous & cruel manner……. The Riot was regularly conceived & planned – no one therefore had any excuse who joined in it: It’s purpose was open & avowed: All that was done was executed deliberately & by great violence: The Individual acts of violence charged agt Black & His son & others to which He pleaded guilty prove very direct action & leading participation in the illegal objects & outrageous conduct of the Mob. That the Magistrates & others may have a strong feeling agt the Irish Catholics & in favour of the Townspeople is very far from recommending in my opinion any Mitigation of this lenient Sentence.” So George Lauder Snr. was not the enlightened champion of the common man that history would have us believe, but rather a friend and apologist for a vile thug who led a mob that committed heinous acts, but he was a clever man with a wealth of experience in hydraulic engineering and would have advised Carnegie of the likely failure of the dam.

George Lauder Jnr. “Dod” For Carnegie’s cousin and surrogate brother, George Lauder Jnr., see above with the rider that unlike his father who was self-taught, Dod had the benefit of a university degree.

Robert Pitcairn Was the Superintendant of the Western Division of PRR when the first disaster struck Johnstown on Friday, September 14, 1866. On that occasion a wooden platform at the PRR’s station there collapsed with a large crowd on it killing 13 and injuring over 300. The PRR had advertised that President Johnson’s electioneering train tour of the area would be stopping at the station and war heroes such as Ulysses S. Grant and David Farragut would be on board. As expected a huge crowd attended and surged forward to see their heroes, upon which the wooden platform collapsed.

Shortly after the 1866 tragedy the Coroner of Cambria County, William Flattery summoned a jury to investigate the cause of death of David Metzgar, a hotel owner of Johnstown who died in the accident and after hearing evidence the jury decided: “The platform was defective and the death was caused by the negligence of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company”. Although the PRR were responsible for urging people to come to the station and view the President from their defective platform, their lawyers, at Pitcairn’s direction, fought a test case for damages through the courts all the way up to the Supreme Court, which, not surprisingly, given the influence of the PRR, dismissed the claim. LINK

One of the earliest members of the Club, Pitcairn gave evidence to the ASCE inquiry that he, like Morrell, had reservations about the modifications to allow road widening that rendered the auxiliary spillway redundant on his former PPR dam, and he (again like Morrell) had his own engineer carry out a report on the rebuilding of the dam, but unfortunately he could not find his report for the inquiry. After the inquiry it transpired that Robert Halliday, an Engineering Superintendent of the Lewiston and Sunbury Division of the PRR, inspected the dam in 1880 and found it unsafe.

Pitcairn’s evidence of his reservations about the modifications to the dam based on his PRR qualified engineer Halliday’s reports is at odds with his confidence in the unqualified President of the Club, Benjamin Ruff, who according to Pitcairn was “better than any engineer”, a misplaced belief that was self-evidently wrong with deadly consequences. However Pitcairn’s defence of Ruff’s competence is probably explained by the fact that both Pitcairn and Ruff were Masonic Knights Templar, a body whose members take vows to protect a fellow knight in distress or when their reputation is impugned. LINK

Pitcairn did not know Carnegie before he came to the USA, as he was from the west of Scotland, Carnegie from the east, but they became boyhood friends when growing up in the tough ‘Slabtown’ area of Allegheny and he remained, by Carnegie’s own admission, his best friend in the USA, so it is inconceivable that he did not impart his reservations about the soundness of the dam to Carnegie. It seems much more likely that he was aware that the dam would fail and benefit his best pal, and given how the powerful PRR were allowed to get away with murder in the 1866 station platform collapse, he would have no worries about legal consequences should the dam failure cause deaths.

Andrew Carnegie

The first thing to say about the accused, Andrew Carnegie, is that he was a glib liar. There are many proven instances of this, but for the purpose of this charge against him it is fitting to look at his part in the Braddock lockout of 1887/8. The myth that Carnegie was a good, paternal even, employer, is based on the fact that he cultivated good relations with the unions that represented the highly skilled puddlers, who were needed to produce wrought iron before the advent of the Bessemer process. That much was true, but with the advent of Bessemer furnaces, which could be operated by unskilled workers with just a few hours training Carnegie had no need to be the worker’s friend.

In 1887 in his new role as master rather than friend he locked out his workers and turned his Braddock steel mill into an armed fortress where armed Pinkertons were barracked. Despite the plethora of evidence to support this fact, Carnegie lied to the Congressional Committee that investigated US Steel in 1912 when he stated under oath that “Pinkerton guards were never employed except when I was away in Europe.” Carnegie spent the entire winter of the Braddock lockout in New York and Pittsburgh, and by his own admission had daily cable communications with Bill Jones his Superintendent there. LINK

It was at Braddock that Carnegie demonstrated that his well known ruthlessness towards poor East European migrants (known as Huns), was meted out equally to one of his own townsfolk, David Gibson. David was a young man in Dunfermline where had heard Carnegie make a speech urging young men to go to Pittsburgh where he would guarantee them jobs and look after them. David took Carnegie at his word, emigrating in 1886 and in December 1887, while employed at Carnegie’s Braddock steel mill he was one of 2,000 workers locked out from December through to April.

In this period the union representing the locked-out men, the Knights of Labor (K.o.L), were presented with an ultimatum that they accept a 10% wage reduction, which they refused. All through the cold winter of 1888 the locked out workers held out and behaved peacefully, but were eventually starved into submission and returned to work on the basis that they agree to a new working agreement, which increased their working day from 8 to 12 hours, 7 days a week, reduced their wages and forbade union membership. Faced with a choice of starve or work, the K.o.L agreed, with a promise from the company’s Superintendent Bill Jones that none would be victimised.

Acting on union advice David reported back for work only to find that his job was one of hundreds that had been filled by scab labour, who, during the lockout had been brought directly into the works on trains escorted by Pinkerton guards armed with Winchester rifles with orders to shoot any union men who interfered. David wrote, to Carnegie pleading for his job back, but to no avail and when he found work with another company contracted to do repairs in the Braddock mill, Carnegie’s manager Bill Jones spotted him one day and made that sub-contractor sack him and had the police remove him from the mill. Given that David was now blacklisted and aware of the influence Carnegie had in the steel industry he had to find work in a new line altogether, as an expressman, and this he did for the rest of his life. LINK

Four years later, in 1892, Carnegie repeated his Braddock tactic of breaking the workers’ unions at his Homestead plant, but unlike the Braddock mill, which had a railway running directly into it which allowed unfettered access for scab labour and Pinkertons, Homestead didn’t have direct rail line to the works. Sited on the banks of the Monongahela River, access was by river barge or road through the town. Nor did Homestead have a passive workforce like Braddock, as the men there were represented by the Amalgamated Association of Iron & Steel Workers (A.A.) which had won an earlier wage cut struggle in 1889 with Carnegie, and they had witnessed how, just a few miles away, their Braddock brothers had been cheated with false promises, and mistreated as “White Slaves” on their return to work. So they were prepared to fight for their jobs.

It is a matter of record that during the Homestead lockout Carnegie absented himself to remote Rannoch Moor in the Scottish Highlands and left his business partner Frick to carry out his plans. He knew the introduction of armed Pinkertons into the mill, would be problematic, with violent confrontations a certainty, and fatalities probable. This prospect didn’t deter Carnegie who knew that hundreds of men’s lives would be ruined by sacking, blacklisting, eviction from company-linked homes and lives would be lost, but he reckoned that was the price worth paying for increased productivity.

Carnegie was as devious at play as he was at work and in today’s politically correct world Andrew Carnegie would probably be charged with having groomed Louise Whitfield, as he knew her first when he was 35 and she was 13 and he continued to see her regularly for the next ten years until his mother died and he married her. Carnegie was an accomplished horseman (his courtship of 13 year old Louise Whitfield began with rides around Central Park, New York).

Adding to Carnegie’s lying, ruthlessness and grooming, he was also the worst possible sort of hypocrite, an avowed pacifist who made his fortune in arming the war machine and while taking no part in his adopted country’s Civil War, saw nothing wrong in paying an agent to hire John Lindew, a poor Irish immigrant to act as surrogate and take his place in the army when, in July 1864 he received his draft notice.

Given the above recorded flaws in Carnegie’s character it must be the case that he knew with certainty that the dam owned by his business partner Frick and shoddily rebuilt by his friend and Club co-owner Ruff would fail one day, and while he didn’t know how many lives would be lost, he reckoned it was a price worth paying if it gave him total dominance of the steel market, which up to then a fully functioning Cambria Iron works had prevented.

Carnegie believed in the after-life, or at least he hedged his bets on it, as exemplified in July 1903 when he considered appointing a Roman Catholic priest as a trustee in his Dunfermline Trust. His chief trustee Dr John Ross dissuaded him of this radical notion in a society where anti-RC sentiment was endemic stating “no priest would care to serve and the Roman Catholics in Dunfermline would not feel such a representation necessary” to which Carnegie replied: “All right, Boss. Exit Holy Father, but I like to keep in with one who can grant absolution. It may be handy someday.”

When he became the richest man in the world, Carnegie considered his philanthropy acted as a counterbalance to his ruthlessness and total disregard for life that he showed while amassing his fortune. This logic was displayed by Carnegie in 1914, when, nearing the age when he expected to go to meet his maker, he attended the 25th anniversary of the first of his USA free library gifts made to the people of Braddock and said in a speech there: “I’m willing to put this library and institution against any other form of benevolence. . . . And all’s well since it is growing better and when I go for a trial for the things done on earth, I think I’ll get a verdict of ‘not guilty’ through my efforts to make the earth a little better than I found it.”

Just as today’s politicians usually only appear before crowds that are sympathetic to them, the crowd Carnegie addressed at Braddock would not have included those he had treated like animals in the winter lockout of 1887/8, nor would it have included his townsman David Gibson, or the hundreds of others, who, sacked and blacklisted, was forced to leave the steel industry and seek a living elsewhere.

Just as today’s politicians usually only appear before crowds that are sympathetic to them, the crowd Carnegie addressed at Braddock would not have included those he had treated like animals in the winter lockout of 1887/8, nor would it have included his townsman David Gibson, or the hundreds of others, who, sacked and blacklisted, was forced to leave the steel industry and seek a living elsewhere.

From his own words (sermon?) at Braddock it seems clear that Carnegie believed that when he appeared before God on The Judgement Day, God would forgive him for the suffering and deaths he caused and allow him into heaven; believed that his malevolence against his workers would be cancelled out by his benevolence in providing free libraries for those who remained employed by him, that is, those who accepted his 12 hour shift, 7 days a week, “White Slave” regime and managed to keep up with their mortgage payments.

[This ends the case for The Prosecution]

The Case for the Defence: Any defence of Carnegie’s role in the Johnstown Flood Disaster must come from conjecture as he never spoke of his stewardship of the dam while a Superintendant with the PRR, or later involvement as the most prominent member of the Club, so it might have been what’s known in the Scots idiom as a ‘didnae ken’, defence, that is, the accused did not know of the crime. It might have been as follows:

I Andrew Carnegie did not suspect the Club dam might fail. On the contrary the advice of partner Henry Frick, Uncle Lauder, George Lauder Jnr. and Robert Pitcairn was that the dam was sound and I had no knowledge of Benjamin Ruff’s modifications being anything other than best practice.

I Andrew Carnegie am a simple, naïve and trusting man with little knowledge of practical matters, which I delegate to others. In business I sought only to gain wealth so that I might disperse it widely spreading sweetness and light in the world.

I Andrew Carnegie was PRR Superintendent in charge of the dam when it failed in 1862, but I was in Dunfermline at the time and Robert Pitcairn, my best friend who took over my duties while I was away said nothing about it. I knew nothing of Robert Pitcairn having the dam inspected when he was PRR Superintendent of the Western Division at the time the Club were rebuilding it, nor am I aware that any PRR engineers reported it as being it unsafe. I have no knowledge of Daniel Morrell’s engineer finding the dam unsafe or of his offering to effect repairs to make it safe at his own cost, or of the Club declining such offer. I simply used my cottage at the club for recreation with my family and took no part in any board meetings or other facility management matters there.

I Andrew Carnegie have no knowledge that Henry Clay Frick stated to my private secretary that we would both go to hell when we died, and if he did, his prediction could not have had anything to do with our actions or omissions at the South Fork Dam, or elsewhere in the steel industry where our actions as employers were exemplary, with the safety of our workmen paramount.

[This ends the case for The Defence]

VERDICT The Court of Historical Truth sitting in Dunfermline in 2024, after considering all of the circumstantial evidence connected with the 1889 dam failure at South Fork, find the accused Andrew Carnegie is: Guilty As Charged.

Recommended reading with the above: The Johnstown Flood, David McCullough , Johnstown’s Flood of 1889, Neil M. Coleman , The Bosses Club, Richard A. Gregory , Andrew Carnegie, David Nasaw , The Johnstown Flood, Casey Goldberg , The South Fork Dam Failure & Johnstown Flood of 1889, Michael D. Bennett